The John Birch Society's "Impeach Earl Warren" Billboards Were Common in the 1960s in the American South

Now, more than ever before, we need to understand the jurisprudential philosophy of constitutional originalism that has been developed by American conservative Republicans over the past fifty years. The effort of the conservative originalists to take control of most of the federal judiciary, including the Supreme Court, has succeeded, for the first time in American history. This effort--led by the Federalist Society--reached its consummation during Donald Trump's presidency.

Of the three Supreme Court justices appointed by Trump--Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett--Gorsuch and Barrett are self-professed originalists, and Kavanaugh is sympathetic to originalism. Justice Clarence Thomas is a proud originalist. Justice Samuel Alito and Chief Justice John Roberts often vote with the originalists. Because of their ages, we can easily imagine that these six justices will be the majority on the Court for at least ten to twenty years. At the time of her confirmation, Barrett was forty-eight years old; and the other conservative justices were fifty-three (Gorsuch), fifty-five (Kavanaugh), sixty-six (Roberts), seventy (Alito) and seventy-two (Thomas). This originalist majority will have many years to radically transform American constitutional politics. They have already begun to do that--particularly with the overturning of Roe v. Wade.

Is the Republican originalist philosophy of the Constitution correct or not? What are the likely consequences (good or bad) of having a Supreme Court controlled by Republican originalism? Is there a good alternative to originalism, such as the idea of the "living constitution" favored by liberal Democrats? Or is there perhaps another form of constitutional originalism that is better than the Republican originalism that has taken over the Court?

I have argued for a Lockean and Lincolnian originalism that interprets the original meaning of the constitutional text in the light of the philosophic principles of the Declaration of Independence and Darwinian natural right. In some respects, this is similar to what Jack Balkin has called "living originalism." Some of my previous posts on this can be found here, here, and here.

I have been thinking about these questions ever since I taught my first constitutional law class at Rosary College (now Dominican University), in River Forest, Illinois, in the fall of 1977. I am now prepared to argue that by comparison with the legal positivism of Republican originalism, the better form of originalism is the legal naturalism of the Lockean constitutional originalism of Abraham Lincoln. Those of you who know the work of Harry Jaffa will recognize his influence here on my thinking, although I am not sure that Jaffa would have fully agreed with my grounding of Lockean/Lincolnian natural rights in Darwinian natural right.

THE LEGAL POSITIVISM OF CONSERVATIVE REPUBLICAN ORIGINALISM

Conservative Republican originalism rests on a positivist understanding of law as ultimately the command of a lawmaker enforced by punishment of those who disobey the law. By contrast, the naturalist understanding of law is that the ultimate standard for legal justice is the natural justice of natural law or natural rights--or "the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God." The legal positivist says that this naturalist understanding confuses the objective judgment of a law's validity and the subjective judgment of a law's morality. The legal positivist recognizes the validity of any law enacted by the lawmaking institutions of a society as an objective fact, in contrast to the subjective value-judgment of that law as good or bad, just or unjust. Consequently, a positivist originalist will say that judges must interpret constitutional laws exactly as they were originally understood by those who wrote and ratified those laws, and the judges must not impose any personal moral judgment of right or wrong, just or unjust. And so, for example, judges must recognize as constitutional rights only those rights expressly enumerated in the Constitution, without claiming any supposedly natural rights that are not expressly enumerated in the constitutional text.

The conservative Republican campaign for positivist constitutional originalism began in 1954 as a reaction against the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education striking down racial segregation in public schools as an unconstitutional violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Newly appointed Chief Justice Earl Warren deftly persuaded a divided court to sign onto a unanimous opinion written by Warren. This was the beginning of the modern civil rights movement for abolishing racial segregation.

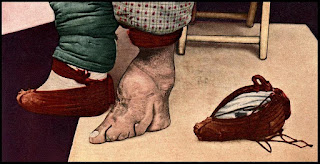

Conservative Republicans and southern Democrats denounced Brown and other decisions attacking segregation as an exercise in political power that was contrary to the text of the Constitution, because those who wrote and ratified the Fourteenth Amendment did not intend that this would forbid racially segregated public schools, and because such decisions violated the constitutional principle of state's rights that allows state governments to enforce racial segregation. The right-wing John Birch Society promoted an "Impeach Earl Warren" campaign that included billboards scattered around roads in the American South. Because of this refusal to accept the Brown decision, many public-school systems remained segregated in the South, even into the late 1960s.

I had some personal experience with this. When my parents moved in 1962 from DeSoto, Missouri, to Wills Point, Texas, I entered an all-white public high school that was separated from the high school for black students, which was different from the racially integrated schools in DeSoto. When my parents then moved in 1964 to Big Spring, Texas, I discovered that Big Spring High School had been one of the few public schools in Texas that became racially integrated immediately after the Brown decision in 1954.

As the alternative to the "judicial activism" of the Warren Court, conservative Republicans insisted that the Supreme Court should adhere to "strict constructionism," so that judges would be guided by the text of the Constitution and the original intent of the Founding Fathers and of those who amended the Constitution, rather than the personal moral and political values of the judges.

The modern history of the movement for an originalist jurisprudence took a new turn in 1971 with the publication of an article in the Indiana Law Review by Robert Bork--"Neutral Principles and Some First Amendment Problems." Initially, this article received little attention. But later, as Bork became a famous proponent of originalism, it became one of the most cited law review articles ever written.

Bork's article was written largely as a response to Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), which Bork identified as "a typical decision of the Warren Court" (7). Griswold struck down as unconstitutional a Connecticut law making it a crime, even for married couples, to use contraceptive devices. The Court said that this law violated the constitutional "right to privacy."

The obvious objection to this claim is that there is no express declaration of a "right to privacy" anywhere in the Constitution. But in his opinion for the Court, Justice William Douglas argued that the right to privacy was within the "penumbras" of the Bill of Rights:

". . . specific guarantees in the Bill of Rights have penumbras, formed by emanations from those guarantees that help give them life and substance. . . . Various guarantees create zones of privacy. The right of association contained in the penumbra of the First Amendment is one, as we have seen. The Third Amendment in its prohibition against the quartering of soldiers 'in any house' in time of peace without the consent of the owner is another facet of that privacy. The Fourth Amendment explicitly affirms the 'right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures.' The Fifth Amendment in its Self-Incrimination Clause enables the citizen to create a zone of privacy which government may not force him to surrender to his detriment. The Ninth Amendment provides: 'The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.'"

Although Douglas did not identify this as a natural right, he came close to saying that in at least one passage: "We deal with a right of privacy older than the Bill of Rights--older than our political parties, older than our school system. Marriage is a coming together for better or for worse, hopefully enduring, and intimate to the degree of being sacred." Is this suggesting that marriage is so deeply rooted in human nature that we should recognize a natural right to marriage--and to the right to make marital decisions such as concerning birth control?

When I first discussed the Griswold decision with my students at Rosary College, I was skeptical about Douglas's appeal to the "penumbras" of the Bill of Rights. Since "penumbra" was not part of my vocabulary, I looked it up in some dictionaries. I learned that it was a word borrowed from Latin meaning "a partially shaded area." According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Oliver Wendell Holmes introduced the penumbra metaphor into constitutional jurisprudence. In The Common Law, Holmes said: "Legal, like natural divisions, however clear in their general outline, will be found on exact scrutiny to end in a penumbra or debatable land." This corresponds to what the OED identifies as the third sense of "penumbra"--"a faint intimation of something or a peripheral region of uncertain extent." The OED also says that Douglas's use of "penumbra" in Griswold is considered "the locus classicus for this usage."

To speak of an unenumerated constitutional right of privacy as a penumbral emanation of the enumerated rights in the Bill of Rights sounds remarkably fuzzy. It's so fuzzy that Bork complained that Griswold was an "unprincipled decision," because the Court was expressing its subjective value judgment endorsing the right of privacy that could not be justified by any objective principle of jurisprudence.

". . . We are left with no idea of the sweep of the right of privacy and hence no notion of the cases to which it may or may not be applied in the future. The truth is that the Court could not reach its result in Griswold through principle. The reason is obvious. Every clash between a minority claiming freedom and a majority claiming power to regulate involves a choice between the gratifications of the two groups. When the Constitution has not spoken, the Court will be able to find no scale, other than its own value preferences, upon which to weigh the respective claims to pleasure. . . ."

"In Griswold a husband and wife assert that they wish to have sexual relations without fear of unwanted children. The law impairs their sexual gratifications. The State can assert, and at one stage in that litigation did assert, that the majority finds the use of contraceptives immoral. Knowledge that it takes place and that the State makes no effort to inhibit it causes the majority anguish, impairs their gratifications."

Bork went on to observe:

". . . Unless we can distinguish forms of gratification, the only course for a principled Court is to let the majority have its way . . . . There is no principled way to decide that one man's gratifications are more deserving of respect than another's or that one form of gratification is more worthy than another. Why is sexual gratification more worthy than moral gratification? . . . There is no way of deciding these matters other than by reference to some system of moral or ethical values that has no objective or intrinsic validity of its own and about which men can and do differ. Where the Constitution does not embody the moral or ethical choice, the judge has no basis other than his own values upon which to set aside the community judgment embodied in the statute. That, by definition, is an inadequate basis for judicial supremacy. . . ."

Bork concluded: "Legislation requires value choice and cannot be principled in the sense under discussion. Courts must accept any value choice the legislature makes unless it clearly runs contrary to a choice made in the framing of the Constitution."

In support of this originalist view of constitutional jurisprudence, Bork spoke in 1982 at the founding meeting of the Federalist Society, which became the preeminent organization for lawyers and law professors who wanted to advance the originalist philosophy of law. This position was strengthened in 1985, when Edwin Meese, Attorney General in the Reagan Administration, gave a speech to the American Bar Association pledging to promote a "jurisprudence of original intention." In 1986, President Reagan appointed Associate Justice William Rehnquist to become the new Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and Antonin Scalia to take his place as a new associate justice. Rehnquist and Scalia became forceful champions of originalism.

In 1987, Reagan nominated Bork for the Supreme Court. Since Bork had been a professor of law at Yale Law School, the Solicitor General of the United States, and a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, he seemed to be so highly qualified that he would be quickly confirmed by the Senate. But the liberal opponents of Bork's originalism decided to launch a national campaign against Bork's confirmation. The twelve days of confirmation hearings, presided over by the young senator from Delaware--Joe Biden--who was chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, were televised, and they captured the attention of the whole country.

Bork was questioned intensely about his opposition to the Griswold decision, because the claim that there was a constitutional right to privacy had become one ground for the decision in Roe v. Wade in 1972 that there was a constitutional right to abortion in the early stages of pregnancy, and the liberal opponents of Bork feared that he would vote to overturn Roe. Bork argued that while the Connecticut law prohibiting contraception was wrong and even silly, this was a political question for the citizens and legislators of Connecticut and not a legal question for the Supreme Court, because there was no express constitutional language about the "right to privacy." He also said that he would respect the Roe decision as a well-established precedent, even if he found the reasoning in Roe weak.

Bork was also questioned about whether his originalist interpretation of the Constitution would have supported Roger Taney's opinion in the Dred Scott case in 1857 upholding slavery as a constitutional right to property. After all, Taney cited those provisions of the Constitution that protected slavery. Senator Howard Metzenbaum quoted from Taney's opinion about protecting slavery as part of the "original intent" of the Framers. Bork's response was to say: "the Devil can quote Scripture." Amazingly, he seemed thereby to concede that Taney was correct in his constitutional originalism. Bork did add, however, that Taney's decision was wrong in usurping the power of Congress by declaring unconstitutional the limitation on the extension of slavery in the Missouri Compromise of 1820.

The Senate rejected Bork's nomination by a vote of forty-two in favor and fifty-eight against. This was one of the biggest defeats for a Supreme Court nominee in American history. Some of Bork's supporters drew from his failure the lesson that he had answered the hostile questions in his confirmation hearings too honestly and directly. Since then, originalist judges nominated to the Supreme Court have been evasive or even deceptive about their views in their confirmation hearings. For example, the justices who voted last summer to overturn Roe had been careful in their confirmation hearings to deceptively create the impression that they would always uphold the precedent of Roe.

Bork could have won confirmation in 1987 if he had reaffirmed what he had said in a 1968 article in Fortune magazine about the Griswold decision, which was very different from what he had said in his 1971 Indiana Law Review article. In that Fortune article, Bork argued:

"A desire for some legitimate form of judicial activism is inherent in a tradition that runs strong and deep in our culture, a tradition that can be called 'Madisonian.' We continue to believe there are some things no majority should be allowed to do to us, no matter how democratically it may decide to do them. A Madisonian system assumes that in wide areas of life a legislative majority is entitled to rule for no better reason than that it is a majority. But it also assumes there are some aspects of life a majority should not control, that coercion in such matters is tyranny, a violation of the individual's natural rights. Clearly, the definition of natural rights cannot be left to either the majority or the minority. In the popular understanding upon which the power of the Supreme Court rests, it is precisely the function of the Court to resolve this dilemma by giving content to the concept of natural rights in case by case interpretations of the Constitution" (170).

At first glance, it might appear that there is nothing in the text of the Constitution to support this, because the term "natural rights" never appears in the Constitution. Nevertheless, Bork argued, Justice Arthur Goldberg, in his concurring opinion in Griswold, could rightly see an implicit appeal to natural rights in the Ninth Amendment: "The enumeration, in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people." Goldberg had explained: "the Ninth Amendment shows a belief of the Constitution's authors that fundamental rights exist that are not expressly enumerated in the first eight amendments . . . and an intent that the list of rights included there not be deemed exhaustive."

At his confirmation hearings, Bork was asked about his view of the Ninth Amendment. Instead of recognizing it as pointing to unenumerated natural rights, as he had in 1968, he dismissed it as a meaningless provision of the Constitution:

"I do not think you can use the Ninth Amendment unless you know something of what it means. For example, if you had an amendment that says 'Congress shall make no,' and then there is an inkblot, and you cannot read the rest of it, and that is the only copy you have, I do not think the court can make up what might be under the inkblot."

As I have said previously, this scorn for the Ninth Amendment illustrates the incoherence of Bork's originalism. On the one hand, originalists insist that every provision of the Constitution must be given some meaning. On the other hand, they throw out the Ninth Amendment because it denies their claim that the Constitution does not protect unenumerated rights.

A coherent originalism could recognize the importance of the Ninth Amendment in pointing to the principles of the Declaration of Independence--the Lockean philosophy of natural rights--as the philosophic foundation for interpreting the Constitution. That was the originalism of Abraham Lincoln that was restated by Harry Jaffa.

LINCOLNIAN ORIGINALISM

"A word fitly spoken is like apples of gold in pictures of silver" (Proverbs 25:11). After Alexander Stephens in a letter reminded Abraham Lincoln of this verse from Proverbs, Lincoln wrote out this passage sometime around January of 1861, shortly before his inauguration as President, and four months before the start of the Civil War with the Confederate firing on Fort Sumter:

"All this is not the result of accident. It has a philosophical cause. Without the Constitution and the Union, we could not have attained the result; but even these, are not the primary cause of our great prosperity. There is something back of these, entwining itself more closely about the human heart. That something, is the principle of 'Liberty to all'--the principle that clears the path for all--gives hope to all--and, by consequence, enterprize, and industry to all."

"The expression of that principle, in our Declaration of Independence, was most happy, and fortunate. Without this, as well as with it, we could have declared our independence of Great Britain; but without it, we could not, I think, have secured our free government and consequent prosperity. No oppressed people will fight, and endure, as our fathers did, without the promise of something better, than a mere change of masters."

"The assertion of that principle, at that time, was the word, 'fitly spoken' which has proved an 'apple of gold' to us. The Union, and the Constitution, are the picture of silver, subsequently framed around it. The picture was made, not to conceal, or destroy the apple; but to adorn, and preserve it. The picture was made for the apple--not the apple for the picture."

"So let us act, that neither picture, or apple shall ever be blurred, or bruised or broken" (Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 4: 168-169).

Although there is no evidence that Lincoln ever used this language in any of his public speeches or writings, its imagery does vividly capture the main idea of his philosophic constitutional originalism: the text of the Constitution is the silver frame around the golden principles of the Declaration of Independence, and thus the original meaning of the constitutional text must be interpreted in the light of the Declaration of Independence and its Lockean philosophy of natural rights.

In some ways, Lincolnian originalist jurisprudence resembles Ronald Dworkin's philosophic moral reading of the Constitution, in which the Constitution is interpreted as expressing the Lockean moral philosophy of the Declaration of Independence.

Jaffa claimed that Bork came close to this Lincolnian originalism in his 1968 article, although he failed to recognize the importance of the Declaration as the authoritative statement of natural rights. But then in his 1971 article and in his 1987 confirmation hearings, Bork turned away from this by embracing a legal positivist interpretation of the Constitution that denied natural rights.

There are two obvious objections to Lincolnian originalism. The first is that the text of the Constitution says nothing about the Declaration of Independence. The second is that the constitutional protections for slavery (the Fugitive Slave Clause, for example) seem to uphold slavery and thus deny the Declaration's fundamental premise that all people are equally free and endowed with rights.

Consider the first objection: when one looks at the constitutional picture framed in silver, one does not in fact see an apple of gold anywhere in the picture! That's what Bork and Scalia said whenever Justice Clarence Thomas invoked the Declaration of Independence in interpreting the Constitution. The Constitution never affirms the Declaration to be part of constitutional law.

There is evidence, however, in the constitutional text and in the history of the American Founding to support Lincoln's claim that there really is an apple of gold in the constitutional picture of silver. Jaffa surveyed this evidence in his book Original Intent and the Framers of the Constitution (1994).

As I have already suggested, the Ninth Amendment's declaration that "the enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people" affirms constitutional protection for unenumerated rights; and to say that these rights are "retained by the people" implies that these rights arose in the Lockean state of nature prior to the establishment of government. This was indicated in Roger Sherman's version of the Ninth Amendment in his original draft of the Bill of Rights: "The people have certain natural rights which are retained by them when they enter into Society." James Madison indicated the same idea when he said that some of the rights protected by the Bill of Rights were "natural rights." One cannot dismiss the Ninth Amendment as an "inkblot" on the Constitution, as Bork did, unless one denies the reality of natural rights.

Moreover, the Preamble of the Constitution also implicitly points to the natural rights of the people in a state of nature. "We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America." By what right did We the People ordain and establish a new government for the United States?

There was already a national government under the Articles of Confederation as ratified by the states in 1781. The delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787 were originally supposed to propose revisions to the Articles of Confederation. But instead of that, they wrote a totally new constitution. In Article 13 of the Articles of Confederation, it was prescribed that any "alteration" of the Articles would have to be approved by the Congress of the United States and by the legislature of each state. But Article 7 of the Constitution prescribed that its ratification would require only the ratification of state conventions in nine states. Thus, the ratification of the Constitution was an unconstitutional overthrow of the Articles of Confederation!

In The Federalist (Number 43), Madison explained that justifying the revolutionary overthrow of the Articles of Confederation and the ratification of the Constitution required an appeal to the principles of the Declaration of Independence--"to the great principle of self-preservation; to the transcendent law of nature and of nature's God, which declares that the safety and happiness of society are the objects at which all political institutions aim, and to which all such institutions must be sacrificed." Thus, the legitimacy of the Constitution as ordained and established by the people depends on affirming the laws of nature and of nature's God as recognized in the Declaration of Independence and as superior to the positive laws of the Articles of Confederation.

Those who framed the Constitution of 1787 and proposed it for ratification by the people in the states saw themselves as reverting to a state of nature in which the people have a natural right to "institute new government." As I have said in some previous posts, those in the First Continental Congress of 1774 also saw themselves as in a Lockean state of nature, with the natural right to revolt from Great Britain and establish new governments for the United States, which they proceeded to do. The Declaration of Independence in 1776 was an affirmation of those "Laws of Nature and of Nature's God" that legitimated what they were doing.

The constitutions of eight of the thirteen original states explicitly affirmed the principles of the Declaration of Independence as the grounding in nature for their right to establish new governments by consent of the people. For example, the Declaration of Rights in the Virginia Constitution proclaimed:

"That all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot by any compact deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety."

Similarly, the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 asserted: "All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights."

This is the language of the Declaration of Independence. And that is why, in 1825, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, speaking for the Board of Visitors of the University of Virginia, recommended to the professors "the Declaration of Independence, as the fundamental act of union of these States" (Jefferson, Writings, Library of America, 479).

A PROSLAVERY CONSTITUTION?

It is true, of course, that the Constitution as it looked before the Civil War amendments (13-15) might seem to contradict the Declaration because of those constitutional provisions protecting slavery as it existed in the slave states. But these were understood by the framers of the Constitution as prudential compromises to win the support of the slave states, with the expectation that over time slavery would be gradually abolished. That explains why, as James Madison observed, the Constitution never uses the words "slaves" or "slavery," Those constitutional provisions pertaining to slaves refer to them as "persons." This points to the inherent contradiction in slavery in treating slaves as both "persons" and "property."

That the Constitution was not really a proslavery document became clear when the Confederate States adopted their new constitution in March of 1861. Remarkably, most of the Confederate Constitution is copied word-for-word from the U.S. Constitution. But if you read them side-by-side, you can see that the drafters of the Confederate Constitution made important changes, and most of these changes are designed to emphatically endorse slavery and to make the right to own slaves as property permanent.

For example, Article I, Section 9, of the U.S. Constitution includes this provision: "No Bill of Attainder or ex post facto Law shall be passed."

Here is the corresponding provision in the Confederate Constitution: "No bill of attainder, ex post facto law, or law denying or impairing the right of property in negro slaves, shall be passed." The Congress of the Confederate States was thus prohibited from passing any law denying or impairing the right of property in negro slaves. The Congress of the United States was not.

Article IV, Section 2, of the U.S. Constitution includes this provision: "The Citizens of each State shall be entitled to all Privileges and Immunities of Citizens in the several States."

Here is the corresponding provision in the Confederate Constitution: "The citizens of each State shall be entitled to all the privileges and immunities of citizens in the several States; and shall have the right of transit and sojourn in any State of this Confederacy, with their slaves and other property; and the right of property in said slavery shall not be thereby impaired." The Congress of the Confederate States was thus prohibited from passing any law denying or impairing the right of slaveholders to take their slaves from one state to another. The Congress of the United States was not.

Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3, of the U. S. Constitution is commonly identified as the "Fugitive Slave Clause." But the term "fugitive slave" does not appear in the text. Here's what it says: "No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due."

Now, here is the version of this clause in the Confederate Constitution: "No slave or other person held to service or labor in any State or Territory of the Confederate States, under the laws thereof, escaping or lawfully carried into another, shall, in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such slave belongs or to whom such service or labor may be due."

Notice how the Confederate Constitution carefully adds the word "slave" twice to the original constitutional text that does not contain this word. This is conclusive evidence that Lysander Spooner was right that fugitive slave laws were unconstitutional because the Constitution's clause about returning fugitives refers not to slaves but to servants--people who were "held to service or labor" by some contractual agreement. A slave is "held" by brute force, not by some legal obligation.

The Confederate Constitution is clearly a proslavery constitution. The U.S. Constitution is not.

This also demonstrates that the primary reason for the secession of the Southern States from the Union was to protect slavery by enacting a constitution that would be reliably proslavery in a way that the U.S. Constitution was not.

This was made clear by Alexander Stephens' famous "Cornerstone Speech." Stephens was the Vice-President of the Confederacy. As a delegate from Georgia, he participated in the drafting of the Confederate Constitution, and he signed it on March 11, 1861. Ten days later, he gave a speech in Savannah, Georgia, explaining the importance of this new constitution for the Confederacy as being superior to the old constitution for the Union.

He explained:

"The new constitution has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution African slavery as it exists amongst us the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution. Jefferson in his forecast, had anticipated this, as the 'rock upon which the old Union would split.' He was right. What was conjecture with him, is now a realized fact. But whether he fully comprehended the great truth upon which that rock stood and stands, may be doubted. The prevailing ideas entertained by him and most of the leading statesmen at the time of the formation of the old constitution, were that the enslavement of the African was in violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically. It was an evil they knew not well how to deal with, but the general opinion of the men of that day was that, somehow or other in the order of Providence, the institution would be evanescent and pass away. This idea, though not incorporated in the constitution, was the prevailing idea at that time. The constitution, it is true, secured every essential guarantee to the institution while it should last, and hence no argument can be justly urged against the constitutional guarantees thus secured, because of the common sentiment of the day. Those ideas, however, were fundamentally wrong. They rested upon the assumption of the equality of races. This was an error. It was a sandy foundation, and the government built upon it fell when the 'storm came and the wind blew.'"

"Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth."

. . .

". . . It is the first government ever instituted upon the principles in strict conformity to nature, and the ordination of Providence, in furnishing the materials of human society. Many governments have been founded upon the principle of the subordination and serfdom of certain classes of the same race; such were and are in violation of the laws of nature. Our system commits no such violation of nature's laws. With us, all of the white race, however high or low, rich or poor, are equal in the eye of the law. Not so with the negro. Subordination is his place. He, by nature, or by the curse against Canaan, is fitted for that condition which he occupies in our system."

The reference here to "the curse against Canaan" refers to Noah's "cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren" (Genesis 9:25). Southern Christians interpreted this as a curse upon the black race in Africa. This was part of a general argument that the Bible ordained slavery. As I have written about this, Fred Ross's Slavery Ordained of God was one of the most influential of the studies of the Bible's support for slavery. Ross denounced Jefferson's Declaration of Independence as an atheistic denial of God's law of human inequality.

It should also be noted that while Stephens was emphatic in his speech in 1861 about the dispute over slavery being the cause of Southern secession, after the Civil War was over, Stephens argued in his Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States (1868) that the secession of the confederate states was only to affirm states' rights, and that slavery was not the cause of the Civil War. He thus contributed one of the primary ideas for the Myth of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy, which sought to glorify the Confederacy as a noble cause. That Myth of the Lost Cause lives on among those Americans today who wave the confederate battle flag as the mythic symbol of the Old South.

As I have indicated in some other posts, the defense of the Confederate Constitution founded on slavery as superior to the U.S. Constitution founded on the principles of the Declaration of Independence continues today among the neoreactionary authoritarians like Curtis Yarvin (Mencius Moldbug).