Since I am teaching a graduate seminar on Thomas Hobbes, I found myself thinking about Hobbes as I watched the State of the Union Address on C-SPAN. This is usually the only time that all of the chief officers of the federal government are in the same room--the members of both Houses of Congress, the President and his Cabinet, the Supreme Court, and the military chiefs. The question for any reader of Hobbes's Leviathan would be: Who's the sovereign?

Considering President Obama's speech, in which he implicitly conceded that he would not be able to do much on his own without the cooperation of Congress, one might conclude that if sovereignty is to be located anywhere, it's to be found in Congress. Looking at the text of the Constitution, and disregarding the history of the Supreme Court's interpretations of the Constitution, one might properly conclude that the clear meaning of the constitutional text favors the sovereignty, or at least supremacy, of the Congress. Remarkably, however, this sovereignty or supremacy of the Congress has rarely been fully recognized or exercised by the Congress itself.

According to Hobbes, in the state of nature without government, human beings have an absolute natural liberty to do anything they can to preserve themselves, but this leads them into a state of war where the lives of all are insecure. To escape that state of war, human beings must consent to the establishment of a State that has the sovereign power to act as a common judge over them for the sake of protecting their lives and securing peace. To protect themselves from foreign enemies and from the injuries of one another, the multitude of individuals must unite their wills into the will of one artificial person--one man or assembly of men--acting as the representative of all the subjects with sovereign power over them for their protection.

There are three kinds of States depending on whether the sovereign power is vested in one person (monarchy), in an assembly of a few selected people (aristocracy), or in a general assembly of all the subjects (democracy) (Leviathan, ch. 19, 121 [129], 125 [133]). Despite these differences in where sovereignty is located, every form of government has the same end--the protection of the lives of the subjects--and the same means to that end--sovereign power that ought to be absolute. Even where there is no sovereign monarch, there can be a "sovereign assembly" (ch. 23, 156-57 [166-67]).

Hobbes admits that allowing a government to have such absolute power has many "evil consequences" or "inconveniences," but the consequences of a weak government, which are all the miseries coming from the perpetual war of everyone against his neighbor, are much worse. In practice, Hobbes concedes, most governments have not had absolute sovereign power, but one should notice, he points out, that these weak governments have not endured for long without falling into disorder and civil war, and that the most enduring governments have been those with all the power necessary for protecting their subjects from both domestic and foreign threats (ch. 20, 136 [144-45]).

By Hobbes's definitions, the American regime is not a democracy but an aristocracy, because American citizens do not rule directly through a general popular assembly (as in Athenian democracy), but rather they elect their representatives. That organization of government through popularly elected representation is prescribed by the Constitution, which serves as what Hobbes calls "fundamental law" (ch. 26, 188-89 [200]).

The Constitution never uses the words "sovereignty" or "sovereign." The principle of sovereignty was affirmed in the Articles of Confederation: "Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled" (Article II). Significantly, the sovereignty of the states was not affirmed in the Constitution. But then the Constitution of the Confederate States of America reversed this change by declaring in its Preamble: "We the people of the Confederate States, each State acting in its sovereign and independent character . . . ."

While the Constitution does not speak directly of sovereignty, it does declare the supremacy of national law over the states. "This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof; and all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding" (Article VI). This supremacy of national law carries with it the supremacy of Congress insofar as "all legislative powers" are vested in the Congress (Article I, sec. 1), and Congress is granted the power "to make all laws" necessary and proper for executing all the powers of the government of the United States (Article I, sec. 8). Moreover, notice that the "supreme-Law" status is not given to the acts of the President or the decisions of the Supreme Court, except insofar as those presidential acts and judicial decisions are sanctioned by congressional legislation.

The supremacy of the Congress as the legislative body is also indicated by the fact that the first and longest article of the Constitution is the legislative article. William Blackstone, in his Commentaries on the Laws of England, declared the common understanding in the eighteenth century that "sovereignty and legislature are indeed convertible terms; one cannot subsist without the other," because "sovereignty" is identified with "the supreme power in a state" for making laws (I, 44, 46). Similarly, Hobbes declared: "The legislator in all commonwealths, is only the sovereign, be he one man, as in a monarchy, or one assembly of men, as in a democracy, or aristocracy. . . . the sovereign is the sole legislator" (ch. 26, 173 [184]).

The second and the second-longest article of the Constitution is the executive article. Even if the Congress was once supreme, it often seems that the growth of presidential power, especially over the past hundred years, has elevated the President over the Congress. One obvious example would be the preeminence of the President in foreign affairs and war. Although the Constitution clearly gives Congress the power to declare war, that congressional power has not been exercised since World War II, and the President has in effect taken over that power. Declaring war was a power of the British Monarch, and it was important for Alexander Hamilton in The Federalist (Number 69) to be able to argue that the American President could not become a King without this power. But now it seems that the President has become almost an elected monarch in his role as Commander in Chief. At any time, however, the Congress could reclaim its power for declaring war. And even when it does not exercise this power, Congress can use its other powers--such as its control over military appropriations--to enforce its will over the President in war.

Hobbes recognized that a "Sovereign Assembly," in times of great disorder or war, could appoint someone as a temporary dictator with the power to deal with the emergency (ch. 19, 125 [133]). In effect, this is what Congress has done. Abraham Lincoln in the Civil War would be the best example of this. But even with his extraordinary powers in the Civil War, Lincoln was constrained by his need for Congress to authorize his actions.

The President participates in the legislative process by making legislative recommendations and through the threat of using his veto power. But any veto can be overridden by a two-thirds vote of the two Houses of Congress. And as we can see with President Obama, any president's legislative agenda can be frustrated by congressional opposition.

Unlike the British Monarch in the seventeenth century, the President has little control over the convening of the legislature. Hobbes believed that a Parliament could be sovereign only if it could not be assembled or dissolved but by its own power (ch. 26, 175 [186]). The American Constitution prescribes that Congress must meet at least once a year, and the two Houses are to prescribe the rules for their own proceedings (Article I, secs. 4-5). The President has the power to convene Congress for special sessions "on extraordinary occasions," and if the two Houses disagree about the time of adjournment, he can set the time of adjournment (Article II, sec. 3).

Moreover, we should never forget the power of the Congress for impeaching the President, which is the ultimate weapon for subordinating the President to the Congress.

The third and third-longest article of the Constitution is the judicial article. If the Constitution is the fundamental law, and if the Supreme Court is the final interpreter of the Constitution, with the power to overturn laws of Congress as unconstitutional, then one might think that, in some sense, this makes the Supreme Court sovereign. Hobbes does say that "the interpretation of the law dependeth on the sovereign power" (ch. 26, 179 [190]).

We should notice, however, that the power of judicial review is not stated in Article III or anywhere else in the Constitution. And even though this power of the Supreme Court has been well-established by tradition, Congress has powers that can be used to work its will against the Court. The Congress can impeach federal judges. The Congress has complete power "to constitute tribunals inferior to the Supreme Court" (Article I, sec. 8). And the Congress controls the appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, which could be used to restrict the exercise of judicial review (Article III, sec. 2).

In the case of Ex parte McCardle (1868), a newspaper editor had challenged the constitutionality of the Reconstruction Acts. After the Supreme Court had heard arguments in the case, the Congress feared that the Court might declare these Acts unconstitutional, and so the Congress repealed the habeas corpus provision that had allowed this issue to be appealed. The Court then had to say that it had no power to decide the case.

In all of these and other ways, the Constitution gives the Congress all the powers necessary to be supreme if not sovereign over all other branches of government. But what's remarkable about this is that the Congress has almost never exercised these powers fully, and as a consequence of the long disuse of its powers, and of the Supreme Court decisions that have endorsed this tradition of disuse, it is now hard for people to see how the text of the Constitution provides for congressional supremacy.

The two scholars who have argued most persuasively for how the constitutional text establishes congressional supremacy are William Crosskey (in Politics and the Constitution in the History of the United States, 2 volumes [University of Chicago Press, 1953]) and George Anastaplo (in The Constitution of 1787: A Commentary [Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989]).

Crosskey collected a massive amount of evidence centered on the reading of the text of the Constitution itself to support his claim that the Constitution establishes national governmental powers under the general legislative power of Congress. He concluded: "The scheme of the Constitution is simple and flexible: general national power, subject only to a few simple limitations, with the state powers, in the main, continuing for any desired local legislation. So, if the Constitution were allowed to operate as the instrument was drawn, the American people could, through Congress, deal with any subject they wished, on a simple, straightforward, nation-wide basis; and all other subjects, they could, in general, leave to the states to handle as the states might desire" (1172).

He recognized, however, that this scheme of the Constitution had not been executed because of the unwillingness of the Congress to exercise fully all of its powers. He dedicated his book "TO THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES IN THE HOPE THAT IT MAY BE LED TO CLAIM AND EXERCISE FOR THE COMMON GOOD OF THE COUNTRY THE POWERS JUSTLY BELONGING TO IT UNDER THE CONSTITUTION." Crosskey's hope has yet to be fulfilled.

George Anastaplo, who studied under Crosskey at the University of Chicago Law School, has reiterated Crosskey's arguments for seeing congressional supremacy in the Constitution. But the work of both Crosskey and Anastaplo has been largely ignored by the scholars of constitutional law.

While I agree that the Constitution does provide for the supremacy of Congressional power, I am still not sure that this constitutional supremacy corresponds to Hobbesian sovereignty. In the American system of separated powers, the supremacy of Congress does not necessarily give it the absolute power that Hobbes thinks is necessary for sovereignty. I wonder whether the American constitutional tradition rejects Hobbes's principle of sovereignty--the idea that any political order must ultimately be ruled by one supreme and absolute power. By contrast with Hobbes, we might see the American Constitution as based on the principle of countervailing power--the idea that political order can arise from a network of separated entities that check and balance one another. (This is the argument of Scott Gordon's Controlling the State: Constitutionalism from Athens to Today [Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999].)

Some of these points are developed in prior posts here, here., here, and here.

Traditionalist conservatives and classical liberals need Charles Darwin. They need him because a Darwinian science of human nature supports Burkean conservatives and Lockean liberals in their realist view of human imperfectibility, and in their commitment to ordered liberty as rooted in natural desires, cultural traditions, and prudential judgments. Arnhart's email address is larnhart1@niu.edu.

Thursday, January 30, 2014

Tuesday, January 21, 2014

Hobbes's Liberal Leviathan and the Rule of the Clan

Much of what Hobbes says in Leviathan sounds surprisingly liberal. The fundamental right of nature is "the Liberty each man hath, to use his own power, as he will himself, for the preservation of his own Nature; that is to say, of his own Life; and consequently, of doing any thing, which in his own Judgment, and Reason, hee shall conceive to be the aptest means thereunto" (ch. 14, 91). Since this natural liberty of each person to live as he pleases leads to war in the state of nature, each person must give up some of his liberty for the sake of peace. But the contract by which this is done is based on the principle of equal liberty--that each person "be contented with so much liberty against other men, as he would allow other men against himselfe" (92). This principle of equal liberty runs throughout the history of classical liberalism, from John Locke to Adam Smith to Herbert Spencer to Friedrich Hayek.

Nevertheless, the picture of the Leviathan on the title page of the book doesn't look very liberal. All the individuals have been fused into one political body in which all stare up at the crowned head of the ruler. Surely this is the picture of an illiberal authoritarian order.

And yet the authority of this sovereign power arises from the consent of all individuals, who have consented to it for the sake of securing their civil liberty as individuals. This sounds a lot like the arguments for republicanism advanced by English parliamentarians and dissenters against the Royalists. When Hobbes wrote Leviathan, he was in Paris with the royal court in exile of Prince Charles (Charles II), whom he had tutored. But a few months after the publication of Leviathan in 1651, Hobbes was excluded from Charles's court, and Hobbes returned to England early in 1652. The royalists charged him with atheism, heresy, and treachery. They were particularly offended by Parts Three and Four of Leviathan, which attacked Anglican doctrine and hierarchy and endorsed a parliamentary plan for churches being independent of both Anglican episcopacy and Presbyterian church government (ch. 47, 479).

Hobbes's difficult position in the English political and theological controversies of his time is conveyed in his letter of dedication for Leviathan: "For in a way beset with those that contend, on one side for too great Liberty, and on the other side for too much Authority, 'tis hard to passe between the points of both unwounded" (3). Hobbes is neither an absolute libertarian nor an absolute authoritarian, because he thinks that securing individual liberty requires centralized state authority.

This points to a problem in classical liberal political thought. On the one hand, liberals want to expand the liberty of individuals by limiting state authority over them. On the other hand, liberals need a powerful state authority that will enforce the conditions for liberal individualism. So like Hobbes, liberals must steer between "too great Liberty" and "too much Authority."

In many countries around the world today--such as Libya, Somalia, Iraq, and Afghanistan--the weakening or failure of central state power has promoted not individual liberty but the rule of clans that deny individual autonomy. When there is no powerful central government to enforce law and order and provide public goods, people will not live as free individuals; rather they will revert back to an ancient tribal form of social order in which people are treated not as individuals but as members of their extended kinship groups. There are good Darwinian reasons for this, having to do with the evolved instincts for kinship, nepotism, and tribalism based on extended real or fictive kinship.

The moral codes of these clan societies will enforce group honor and suppress individual liberty. For example, clan societies will enforce the blood feuds, the honor killings, and the attacks on infidels that liberals abhor. The social order of liberal individualism will not prevail unless there is a powerful liberal state that will deny the customary legal systems of clan groups and protect the autonomy of individuals from coercion by clans.

That's the message of a brilliant new book--Mark Weiner's The Rule of the Clan (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013). Although he never directly mentions Hobbes, Weiner's argument is Hobbesian in making the case for a Liberal Leviathan. He disputes the common libertarian assumption that liberty is strongest when the state is weakest or even absent. While conceding that the state can be used for illiberal ends, he insists that individual freedom cannot exist if it is not enforced by a powerful liberal state. He develops this argument by showing how weak or failed states have often created a vacuum of power that has been filled by the rule of clans that deny individual liberty.

Weiner represents a liberal society in a visual diagram--the state is a large circle and within this circle smaller circles represent discrete individuals who are equal in their independence (7). This diagram is similar to Hobbes's picture of Leviathan as a single body composed of the discrete bodies of individual citizens.

In contrast to such a liberal society, in which individuals are understood to be equally independent of one another, a clan society assumes that individuals have no identity or value except as members of their extended families. So Weiner's diagram for such a clan society is a big circle around smaller circles representing kin groups that contain even smaller circles that represent individuals who have no independent identity outside of their kin group (9).

A clan society is natural for human beings, Weiner claims, because it is rooted in their instinctive longings for communal life in extended clan groups. And therefore, when there is no powerful liberal state to enforce the legal norms of liberal individualism, the rule of the clan will naturally assert itself. A liberal society cannot exist except as an artificial construction of a liberal state.

Weiner adopts Henry Sumner Maine's account of legal evolution as moving "from Status to Contract," from social orders based on extended family groups to social orders based on free individuals (10-14). This is a movement from clan society to liberal society.

Most of Weiner's book develops this argument through historical case studies of clan societies and of how the centralization of state power is required to restrain clan power and protect individual liberty. His historical cases include the Nuer of Southern Sudan, Medieval Iceland, the early history of Islam, Anglo-Saxon England, the Palestinian Authority, India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

Although I am persuaded by most of what Weiner argues, I am not persuaded by his general assumption that a clan society is more natural or instinctive than a liberal society, and consequently that a liberal society arises only as an artificial imposition by a centralized state that represses the tribal instincts of clan society. I disagree with this for the same reasons that I disagree with Friedrich Hayek's Freudian view that liberal civilization requires the repression of the evolved tribal instincts of human nature.

Like Hayek, Weiner views Marxist socialism as an attempt to overcome liberal individualism by reviving, in a higher form, the social solidarity of ancient clan groups. This is most evident in Friedrich Engels's adoption of Lewis Henry Morgan's theory of the circular evolution of human society, so that eventually modern civilization would evolve into a higher form of Iroquois clan society. The consequences of this kind of thinking were disastrous: "The centralization of political authority in the Communist Party, the abolition of private property, the nightmare of Soviet state surveillance--all were part of an effort to re-create a world of clan solidarity through force of law. The effort ended in slavery, in a new, modernist society of Status that subsumed the individual into the demands of the group" (183).

But if clan solidarity is naturally instinctive for all human beings, and if individual liberty is a artificial invention of modernity that runs against our human nature, then why didn't the Marxist experiment succeed?

Even if there is a natural yearning for clan solidarity, a liberal society can satisfy that yearning by channeling it into the natural and voluntary associations of a pluralist society. Weiner recognizes that in his account of how Walter Scott used his romantic historical novel--Waverley (1814)--to imaginatively recreate the life of Scotland's Highland clans in a way that was compatible with liberal society (188-95). A liberal legal order in Scotland must deny the coercive legal authority of Scottish clans, but that liberal legal order could allow people to celebrate their clan identity as something to be celebrated in memory. Scottish clan identity could become a voluntary commitment in a free society of individuals, in which Scottish clan life became a cultural activity in liberal society without the coercive harshness of the originally illiberal clan society.

I have developed this idea in my comments on Jonathan Haidt's evolutionary moral psychology, in arguing that a classical liberal regime can create a largely open society in which all six of the moral foundations identified by Haidt can be satisfied--not only the individualistic principles of harm, liberty, and fairness, but also the communitarian principles of authority, loyalty, and sanctity.

Moreover, the powerful appeal of liberal culture--even to people in long-established clan societies--suggests that the desire for individual liberty is just as naturally instinctive as the desire for clan solidarity. Weiner disagrees. He thinks that the clan expresses "a basic human drive," which is a "natural drive of human beings . . . to create legal structures in which individual freedom is diminished" (169). He thinks this must be so because "for most of human history, the primary . . . group has been the extended family, the clan," thus, "the clan is a natural form of social and legal organization," and "we humans naturally build legal structures based on real or fictive kin ties or social networks that behave much like ancient clans" (7). In contrast to this evolved instinctive drive to clan society, the modern liberal state is an artificial invention that requires repression of clan instincts.

Weiner is mistaken in claiming that "for most of human history, the primary group has been the extended family, the clan." In fact, for most of our evolutionary history, our human ancestors lived as clanless foragers in bands of nuclear families and small kinship groups. In one brief passage of this book, Weiner recognizes that clan societies did not arise until human beings shifted from small bands of hunter-gatherers to larger tribes of pastoralists (58). But then in the rest of the book, he ignores this and assumes that clan societies have ruled over most of human history.

As I have indicated in some other posts, hunting-gathering foragers probably showed the kind of individual liberty that Hobbes and Locke depict as characteristic of the state of nature. If that is so, then modern liberal individualism could be understood as a revival in modern form of the individualistic life of our Paleolithic ancestors, and thus modern liberal society could appeal to our ancient evolved instincts for individual liberty. This has been argued by Jonathan Turner and Alexandra Maryanski (in The Social Cage [1992] and On the Origin of Societies by Natural Selection [2008])and by Paul Rubin (in Darwinian Politics [2002]).

If this is correct, then the Liberal Leviathan could appeal to all of us as the design for a civil society in which we can satisfy our ancient natural desire for individual liberty.

Also, we can see here the grounds for the debate between liberalism and anarchism, which has been the subject of some previous posts. The liberal assumes that since the natural liberty of individuals in a society without a state leads to war, we need a state to secure peace in a way that promotes as much liberty as is compatible with security. The anarchist assumes that a stateless society can become a self-regulating or self-governing order that secures the conditions for peaceful cooperation without any need for a Leviathan state.

Resolving this debate depends on an empirical science of political anthropology to answer certain questions. How successful have stateless societies been in securing both liberty and security? Have liberal state societies been more successful at this? Even if stateless societies have been somewhat successful in the past--in small forager bands and in larger clans and tribes--how successful can they be for organizing the large nations and extended orders of modern life? Don't the stateless clan societies that we see in the world today suppress individual liberty rather than promote it, as Weiner argues?

This debate has practical implications for the future of global politics. In many parts of the world, states are failing or disappearing. Some observers foresee that the modern state itself is in decline. Liberals will insist that we must preserve the modern state and direct it to liberal ends. Anarchists will say that we should let the modern state fall and then look for new forms of stateless social order to secure our liberty and our security.

Mark Weiner has an essay at "Cato Unbound" on "The Paradox of Modern Individualism."

Elaboration of these points can be found in other posts here, here, here, here, here, here, and here.

Nevertheless, the picture of the Leviathan on the title page of the book doesn't look very liberal. All the individuals have been fused into one political body in which all stare up at the crowned head of the ruler. Surely this is the picture of an illiberal authoritarian order.

And yet the authority of this sovereign power arises from the consent of all individuals, who have consented to it for the sake of securing their civil liberty as individuals. This sounds a lot like the arguments for republicanism advanced by English parliamentarians and dissenters against the Royalists. When Hobbes wrote Leviathan, he was in Paris with the royal court in exile of Prince Charles (Charles II), whom he had tutored. But a few months after the publication of Leviathan in 1651, Hobbes was excluded from Charles's court, and Hobbes returned to England early in 1652. The royalists charged him with atheism, heresy, and treachery. They were particularly offended by Parts Three and Four of Leviathan, which attacked Anglican doctrine and hierarchy and endorsed a parliamentary plan for churches being independent of both Anglican episcopacy and Presbyterian church government (ch. 47, 479).

Hobbes's difficult position in the English political and theological controversies of his time is conveyed in his letter of dedication for Leviathan: "For in a way beset with those that contend, on one side for too great Liberty, and on the other side for too much Authority, 'tis hard to passe between the points of both unwounded" (3). Hobbes is neither an absolute libertarian nor an absolute authoritarian, because he thinks that securing individual liberty requires centralized state authority.

This points to a problem in classical liberal political thought. On the one hand, liberals want to expand the liberty of individuals by limiting state authority over them. On the other hand, liberals need a powerful state authority that will enforce the conditions for liberal individualism. So like Hobbes, liberals must steer between "too great Liberty" and "too much Authority."

In many countries around the world today--such as Libya, Somalia, Iraq, and Afghanistan--the weakening or failure of central state power has promoted not individual liberty but the rule of clans that deny individual autonomy. When there is no powerful central government to enforce law and order and provide public goods, people will not live as free individuals; rather they will revert back to an ancient tribal form of social order in which people are treated not as individuals but as members of their extended kinship groups. There are good Darwinian reasons for this, having to do with the evolved instincts for kinship, nepotism, and tribalism based on extended real or fictive kinship.

The moral codes of these clan societies will enforce group honor and suppress individual liberty. For example, clan societies will enforce the blood feuds, the honor killings, and the attacks on infidels that liberals abhor. The social order of liberal individualism will not prevail unless there is a powerful liberal state that will deny the customary legal systems of clan groups and protect the autonomy of individuals from coercion by clans.

That's the message of a brilliant new book--Mark Weiner's The Rule of the Clan (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013). Although he never directly mentions Hobbes, Weiner's argument is Hobbesian in making the case for a Liberal Leviathan. He disputes the common libertarian assumption that liberty is strongest when the state is weakest or even absent. While conceding that the state can be used for illiberal ends, he insists that individual freedom cannot exist if it is not enforced by a powerful liberal state. He develops this argument by showing how weak or failed states have often created a vacuum of power that has been filled by the rule of clans that deny individual liberty.

Weiner represents a liberal society in a visual diagram--the state is a large circle and within this circle smaller circles represent discrete individuals who are equal in their independence (7). This diagram is similar to Hobbes's picture of Leviathan as a single body composed of the discrete bodies of individual citizens.

In contrast to such a liberal society, in which individuals are understood to be equally independent of one another, a clan society assumes that individuals have no identity or value except as members of their extended families. So Weiner's diagram for such a clan society is a big circle around smaller circles representing kin groups that contain even smaller circles that represent individuals who have no independent identity outside of their kin group (9).

A clan society is natural for human beings, Weiner claims, because it is rooted in their instinctive longings for communal life in extended clan groups. And therefore, when there is no powerful liberal state to enforce the legal norms of liberal individualism, the rule of the clan will naturally assert itself. A liberal society cannot exist except as an artificial construction of a liberal state.

Weiner adopts Henry Sumner Maine's account of legal evolution as moving "from Status to Contract," from social orders based on extended family groups to social orders based on free individuals (10-14). This is a movement from clan society to liberal society.

Most of Weiner's book develops this argument through historical case studies of clan societies and of how the centralization of state power is required to restrain clan power and protect individual liberty. His historical cases include the Nuer of Southern Sudan, Medieval Iceland, the early history of Islam, Anglo-Saxon England, the Palestinian Authority, India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

Although I am persuaded by most of what Weiner argues, I am not persuaded by his general assumption that a clan society is more natural or instinctive than a liberal society, and consequently that a liberal society arises only as an artificial imposition by a centralized state that represses the tribal instincts of clan society. I disagree with this for the same reasons that I disagree with Friedrich Hayek's Freudian view that liberal civilization requires the repression of the evolved tribal instincts of human nature.

Like Hayek, Weiner views Marxist socialism as an attempt to overcome liberal individualism by reviving, in a higher form, the social solidarity of ancient clan groups. This is most evident in Friedrich Engels's adoption of Lewis Henry Morgan's theory of the circular evolution of human society, so that eventually modern civilization would evolve into a higher form of Iroquois clan society. The consequences of this kind of thinking were disastrous: "The centralization of political authority in the Communist Party, the abolition of private property, the nightmare of Soviet state surveillance--all were part of an effort to re-create a world of clan solidarity through force of law. The effort ended in slavery, in a new, modernist society of Status that subsumed the individual into the demands of the group" (183).

But if clan solidarity is naturally instinctive for all human beings, and if individual liberty is a artificial invention of modernity that runs against our human nature, then why didn't the Marxist experiment succeed?

Even if there is a natural yearning for clan solidarity, a liberal society can satisfy that yearning by channeling it into the natural and voluntary associations of a pluralist society. Weiner recognizes that in his account of how Walter Scott used his romantic historical novel--Waverley (1814)--to imaginatively recreate the life of Scotland's Highland clans in a way that was compatible with liberal society (188-95). A liberal legal order in Scotland must deny the coercive legal authority of Scottish clans, but that liberal legal order could allow people to celebrate their clan identity as something to be celebrated in memory. Scottish clan identity could become a voluntary commitment in a free society of individuals, in which Scottish clan life became a cultural activity in liberal society without the coercive harshness of the originally illiberal clan society.

I have developed this idea in my comments on Jonathan Haidt's evolutionary moral psychology, in arguing that a classical liberal regime can create a largely open society in which all six of the moral foundations identified by Haidt can be satisfied--not only the individualistic principles of harm, liberty, and fairness, but also the communitarian principles of authority, loyalty, and sanctity.

Moreover, the powerful appeal of liberal culture--even to people in long-established clan societies--suggests that the desire for individual liberty is just as naturally instinctive as the desire for clan solidarity. Weiner disagrees. He thinks that the clan expresses "a basic human drive," which is a "natural drive of human beings . . . to create legal structures in which individual freedom is diminished" (169). He thinks this must be so because "for most of human history, the primary . . . group has been the extended family, the clan," thus, "the clan is a natural form of social and legal organization," and "we humans naturally build legal structures based on real or fictive kin ties or social networks that behave much like ancient clans" (7). In contrast to this evolved instinctive drive to clan society, the modern liberal state is an artificial invention that requires repression of clan instincts.

Weiner is mistaken in claiming that "for most of human history, the primary group has been the extended family, the clan." In fact, for most of our evolutionary history, our human ancestors lived as clanless foragers in bands of nuclear families and small kinship groups. In one brief passage of this book, Weiner recognizes that clan societies did not arise until human beings shifted from small bands of hunter-gatherers to larger tribes of pastoralists (58). But then in the rest of the book, he ignores this and assumes that clan societies have ruled over most of human history.

As I have indicated in some other posts, hunting-gathering foragers probably showed the kind of individual liberty that Hobbes and Locke depict as characteristic of the state of nature. If that is so, then modern liberal individualism could be understood as a revival in modern form of the individualistic life of our Paleolithic ancestors, and thus modern liberal society could appeal to our ancient evolved instincts for individual liberty. This has been argued by Jonathan Turner and Alexandra Maryanski (in The Social Cage [1992] and On the Origin of Societies by Natural Selection [2008])and by Paul Rubin (in Darwinian Politics [2002]).

If this is correct, then the Liberal Leviathan could appeal to all of us as the design for a civil society in which we can satisfy our ancient natural desire for individual liberty.

Also, we can see here the grounds for the debate between liberalism and anarchism, which has been the subject of some previous posts. The liberal assumes that since the natural liberty of individuals in a society without a state leads to war, we need a state to secure peace in a way that promotes as much liberty as is compatible with security. The anarchist assumes that a stateless society can become a self-regulating or self-governing order that secures the conditions for peaceful cooperation without any need for a Leviathan state.

Resolving this debate depends on an empirical science of political anthropology to answer certain questions. How successful have stateless societies been in securing both liberty and security? Have liberal state societies been more successful at this? Even if stateless societies have been somewhat successful in the past--in small forager bands and in larger clans and tribes--how successful can they be for organizing the large nations and extended orders of modern life? Don't the stateless clan societies that we see in the world today suppress individual liberty rather than promote it, as Weiner argues?

This debate has practical implications for the future of global politics. In many parts of the world, states are failing or disappearing. Some observers foresee that the modern state itself is in decline. Liberals will insist that we must preserve the modern state and direct it to liberal ends. Anarchists will say that we should let the modern state fall and then look for new forms of stateless social order to secure our liberty and our security.

Mark Weiner has an essay at "Cato Unbound" on "The Paradox of Modern Individualism."

Elaboration of these points can be found in other posts here, here, here, here, here, here, and here.

Monday, January 20, 2014

Hobbes and Somalia: Is Anarchy Better Than a Predatory Government?

Is it true, as Hobbes declares in chapter 13 of Leviathan, that the state of nature, where there is no government, must be a state of war where human life is "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short"?

Hobbes presents this as an empirical claim based on five kinds of evidence. First, it's an inference from what we know about the human passions that lead to conflict. Second, it's confirmed by our personal experience when we lock the doors of our houses at night. Third, it's supported by what we know about the savage life of the American Indians living without government. Fourth, we can predict that when any people lose their government, they will fall into civil war. Finally, international politics shows the governments of the world to be either at war or in a posture of war because there is no common power over them to keep peace.

Much of the history of modern political philosophy has turned on the debate over this Hobbesian teaching about the state of nature. And it's an illustration of how debates in political philosophy ultimately depend on empirical claims that can be verified or falsified by the scientific study of political psychology, political anthropology, and political history. A biopolitical science would embrace all of this.

So, for example, an evolutionary political anthropology would deny Hobbes's assertion that human life in a state of nature is "solitary." Human beings have never lived as asocial animals. For most of our evolutionary history, our ancestors lived as hunting-gathering foragers organized as small bands of people bound together by kinship ties and with some informal and episodic leadership. This suggests that Hobbes was wrong in denying Aristotle's claim that human beings are by nature political animals.

But there is some ambiguity about this in Hobbes's writing. For instance, Hobbes says that "the savage people in many places of America, except the government of small Families, the concord whereof dependeth on natural lust, have no government at all; and live at this day in that brutish manner, as I said before" (89). If families have some kind of government, then how can he say that they have "no government at all"? In Hobbes's Latin translation of Leviathan, he writes: "Are there not many places where people live so today? The people of America live so, except that they are subject to paternal laws in small families; and the concord of those families is sustained only by the similarity of their desires." So here he clearly recognizes "paternal laws" as constituting a kind of government based on kinship. He even acknowledges that a large family that is not part of a commonwealth might be considered "a little Monarchy" (ch. 20, 142; ch. 22, 163; ch. 30, 235).

Hobbes also suggests that even where there is no "Commonwealth" to set a "common Rule of Good and Evil," such a rule can be set by "an Arbitrator or Judge, whom men disagreeing shall by consent set up, and make his sentence the Rule thereof" (ch. 6, 39). And one of the laws of nature specified by Hobbes is to submit controversies to the judgment of an arbitrator (ch. 15, 105, 109). Indeed, in bands of foragers, it is common for some influential individuals to act as arbitrators in mediating disputes, which shows an informal kind of governmental leadership. If "anarchy" literally means "no ruler," then human beings have never lived in anarchy, although they have often lived without a centralized state.

But even if Hobbes concedes that human beings can live in ordered societies with customary laws but without a centralized state to enforce a formal system of law, his argument seems to be that societies without a centralized sovereign state tend to be unstable and inclined to fall into civil war. Even if life in a stateless society is not solitary, it is "poor, nasty, brutish, and short."

Hobbes's argument seems to be supported by political scientists today who talk about the problems that come with weak or failed states--like Somalia, for example. Any yet, Peter Leeson, an economist at George Mason University, has argued that the recent history of Somalia actually shows how life in a stateless anarchy can be better than life under a predatory government.

In 1960, the Republic of Somalia was formed as a independent country uniting what had been British Somaliland and Italian Somalia. Then, in 1969, Major-General Mohamed Siad Barre led a military coup that overthrew the democratic government of Somalia and established a military dictatorship that became a socialist dictatorship. All land and most of the industrial and financial property was nationalized. The government was repressive in denying all civil and political liberty, in suppressing all opposition to the government, and in promoting the power of Barre and those he favored. Somalia is divided into clans, and Barre used the government to advance the interests of his clan (the Marehan) over other clans.

In 1991, Somalia's government collapsed, the country fell into civil war, and there was no central government at all. After twenty years of being stateless, the leaders of Somalia's clans finally agreed to a new constitution in 2012, which established a parliamentary government. And yet it's unclear whether the new government can maintain its power in the face of continuing factional conflict among the powerful warlords and clans.

Although this might seem to confirm Hobbes's warning about the propensity of stateless societies to fall into a war of all against all, Leeson claims that "Somalis are better off under anarchy than they were under government." His evidence for this is that many economic and social indicators--such as life expectancy, health care, extreme poverty, and economic production--show that life in Somalia is better than it was under Barre's predatory government.

Leeson is mistaken, however, in identifying this stateless condition of Somalia as a situation of anarchy with no government. As he indicates, Somalia has had a legal system based on private, customary law enforced by clan leaders, with security provided by clan militias. Thus, Somalia has had a kind of government--the government that comes from the rule of clans, which has prevailed in many societies throughout human history.

Leeson refuses to recognize this as government because there is no "monopoly on the law or its legitimate enforcement" (700). He simply assumes that government must be identified as a Hobbesian Leviathan state with a centralized, monopolistic claim on the legitimate use of force. He thus ignores the fact that most human societies have been governed by very decentralized forms of government, including "the government of small families" in foraging bands and the government of extended families in clan societies.

Strictly speaking, anarchy is impossible, if we define it as a total absence of any form of governance. Those who identify themselves as anarchist theorists implicitly recognize this, because what they defend as anarchy is actually a society that is stateless but governed by voluntary associations. Similarly, Leeson seems to defend anarchy broadly defined as stateless self-governance. In Peter Marshall's grand history of anarchist thinkers and movements, he indicates that anarchists distinguish society and the State and defend society as a self-regulating order. He explains: "Pure anarchy in the sense of a society with no concentration of force and no social controls has probably never existed. Stateless societies and peasant societies employ sanctions of approval and disapproval, the offer of reciprocity and the threat of its withdrawal, as instruments of social control" (12-13).

Leeson rightly identifies Somalia as a possible example of how a stateless society might be better for its members than a predatory government that oppresses them. But he also recognizes that it would be even better for Somalia to have a liberal state with limited powers for protecting life and property and providing public goods for the common welfare.

Would it be possible and desirable for a country like Somalia to move from a clan society to a liberal state? Or would the move to liberal individualism require a costly loss of the moral solidarity that comes from the communal life of a clan society? Would this require, as Friedrich Hayek argued, a painful suppression of those natural human instincts that favor the social life of clans or tribes based on ties of extended kinship?

Those questions will be the subject of my next post.

REFERENCES

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, ed. Richard Tuck (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

Peter T. Leeson, "Better Off Stateless: Somalia Before and After Government Collapse," Journal of Comparative Economics 35 (2007): 689-710.

Peter Marshall, Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2010).

Some related posts can be found here, here, here, and here.

Hobbes presents this as an empirical claim based on five kinds of evidence. First, it's an inference from what we know about the human passions that lead to conflict. Second, it's confirmed by our personal experience when we lock the doors of our houses at night. Third, it's supported by what we know about the savage life of the American Indians living without government. Fourth, we can predict that when any people lose their government, they will fall into civil war. Finally, international politics shows the governments of the world to be either at war or in a posture of war because there is no common power over them to keep peace.

Much of the history of modern political philosophy has turned on the debate over this Hobbesian teaching about the state of nature. And it's an illustration of how debates in political philosophy ultimately depend on empirical claims that can be verified or falsified by the scientific study of political psychology, political anthropology, and political history. A biopolitical science would embrace all of this.

So, for example, an evolutionary political anthropology would deny Hobbes's assertion that human life in a state of nature is "solitary." Human beings have never lived as asocial animals. For most of our evolutionary history, our ancestors lived as hunting-gathering foragers organized as small bands of people bound together by kinship ties and with some informal and episodic leadership. This suggests that Hobbes was wrong in denying Aristotle's claim that human beings are by nature political animals.

But there is some ambiguity about this in Hobbes's writing. For instance, Hobbes says that "the savage people in many places of America, except the government of small Families, the concord whereof dependeth on natural lust, have no government at all; and live at this day in that brutish manner, as I said before" (89). If families have some kind of government, then how can he say that they have "no government at all"? In Hobbes's Latin translation of Leviathan, he writes: "Are there not many places where people live so today? The people of America live so, except that they are subject to paternal laws in small families; and the concord of those families is sustained only by the similarity of their desires." So here he clearly recognizes "paternal laws" as constituting a kind of government based on kinship. He even acknowledges that a large family that is not part of a commonwealth might be considered "a little Monarchy" (ch. 20, 142; ch. 22, 163; ch. 30, 235).

Hobbes also suggests that even where there is no "Commonwealth" to set a "common Rule of Good and Evil," such a rule can be set by "an Arbitrator or Judge, whom men disagreeing shall by consent set up, and make his sentence the Rule thereof" (ch. 6, 39). And one of the laws of nature specified by Hobbes is to submit controversies to the judgment of an arbitrator (ch. 15, 105, 109). Indeed, in bands of foragers, it is common for some influential individuals to act as arbitrators in mediating disputes, which shows an informal kind of governmental leadership. If "anarchy" literally means "no ruler," then human beings have never lived in anarchy, although they have often lived without a centralized state.

But even if Hobbes concedes that human beings can live in ordered societies with customary laws but without a centralized state to enforce a formal system of law, his argument seems to be that societies without a centralized sovereign state tend to be unstable and inclined to fall into civil war. Even if life in a stateless society is not solitary, it is "poor, nasty, brutish, and short."

Hobbes's argument seems to be supported by political scientists today who talk about the problems that come with weak or failed states--like Somalia, for example. Any yet, Peter Leeson, an economist at George Mason University, has argued that the recent history of Somalia actually shows how life in a stateless anarchy can be better than life under a predatory government.

In 1960, the Republic of Somalia was formed as a independent country uniting what had been British Somaliland and Italian Somalia. Then, in 1969, Major-General Mohamed Siad Barre led a military coup that overthrew the democratic government of Somalia and established a military dictatorship that became a socialist dictatorship. All land and most of the industrial and financial property was nationalized. The government was repressive in denying all civil and political liberty, in suppressing all opposition to the government, and in promoting the power of Barre and those he favored. Somalia is divided into clans, and Barre used the government to advance the interests of his clan (the Marehan) over other clans.

In 1991, Somalia's government collapsed, the country fell into civil war, and there was no central government at all. After twenty years of being stateless, the leaders of Somalia's clans finally agreed to a new constitution in 2012, which established a parliamentary government. And yet it's unclear whether the new government can maintain its power in the face of continuing factional conflict among the powerful warlords and clans.

Although this might seem to confirm Hobbes's warning about the propensity of stateless societies to fall into a war of all against all, Leeson claims that "Somalis are better off under anarchy than they were under government." His evidence for this is that many economic and social indicators--such as life expectancy, health care, extreme poverty, and economic production--show that life in Somalia is better than it was under Barre's predatory government.

Leeson is mistaken, however, in identifying this stateless condition of Somalia as a situation of anarchy with no government. As he indicates, Somalia has had a legal system based on private, customary law enforced by clan leaders, with security provided by clan militias. Thus, Somalia has had a kind of government--the government that comes from the rule of clans, which has prevailed in many societies throughout human history.

Leeson refuses to recognize this as government because there is no "monopoly on the law or its legitimate enforcement" (700). He simply assumes that government must be identified as a Hobbesian Leviathan state with a centralized, monopolistic claim on the legitimate use of force. He thus ignores the fact that most human societies have been governed by very decentralized forms of government, including "the government of small families" in foraging bands and the government of extended families in clan societies.

Strictly speaking, anarchy is impossible, if we define it as a total absence of any form of governance. Those who identify themselves as anarchist theorists implicitly recognize this, because what they defend as anarchy is actually a society that is stateless but governed by voluntary associations. Similarly, Leeson seems to defend anarchy broadly defined as stateless self-governance. In Peter Marshall's grand history of anarchist thinkers and movements, he indicates that anarchists distinguish society and the State and defend society as a self-regulating order. He explains: "Pure anarchy in the sense of a society with no concentration of force and no social controls has probably never existed. Stateless societies and peasant societies employ sanctions of approval and disapproval, the offer of reciprocity and the threat of its withdrawal, as instruments of social control" (12-13).

Leeson rightly identifies Somalia as a possible example of how a stateless society might be better for its members than a predatory government that oppresses them. But he also recognizes that it would be even better for Somalia to have a liberal state with limited powers for protecting life and property and providing public goods for the common welfare.

Would it be possible and desirable for a country like Somalia to move from a clan society to a liberal state? Or would the move to liberal individualism require a costly loss of the moral solidarity that comes from the communal life of a clan society? Would this require, as Friedrich Hayek argued, a painful suppression of those natural human instincts that favor the social life of clans or tribes based on ties of extended kinship?

Those questions will be the subject of my next post.

REFERENCES

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, ed. Richard Tuck (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

Peter T. Leeson, "Better Off Stateless: Somalia Before and After Government Collapse," Journal of Comparative Economics 35 (2007): 689-710.

Peter Marshall, Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2010).

Some related posts can be found here, here, here, and here.

Sunday, January 19, 2014

Hobbes's Pictures of Leviathan and Liberty

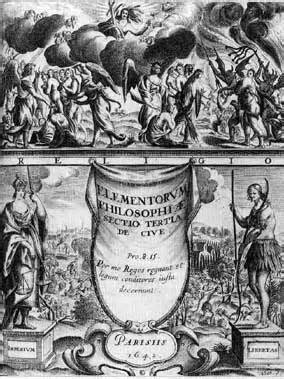

This is the most famous picture in the history of political philosophy, which is the title page for Thomas Hobbes' Leviathan, or The Matter, Forme, and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civill (1651).

As indicated by the Biblical quotation at the very top of the picture--from Job 41:33--Hobbes compares sovereign political power to the Leviathan (probably a giant whale) who is said by God to be so powerful that no power on earth can be compared with him, and he rules as "King of all the children of pride."

In the top half of the picture, Leviathan is depicted as a king holding a staff of authority in his left hand and a sword in his right. The king's body is composed of the human bodies of his subjects, who have their backs turned to the reader as they stare upward at the king's face. Below the king is a settled countryside and a walled city with various buildings, including a church on the king's left side and a fortress on his right.

In the bottom half of the picture, we see the title of the book, and corresponding to the title's indication of a "Commonwealth Ecclesiaticall and Civill," we see a panel of pictures under the king's left arm depicting ecclesiastical authority, and a panel of pictures under his right arm depicting military power and warfare. The ecclesiastical pictures show, at the bottom, a theological dispute. Above that, we see a pair of horns named "Dilemma," a trident named "Syllogism," and three two-pronged forks with the prongs named "Spiritual"/"Temporal," "Direct"/"Indirect," and "Real"/"Intentional." Above that, we see a picture of thunderbolts, perhaps reflecting the phrase of the time concerning "the thunderbolt of excommunication." (Noel Malcolm has suggested this in his magisterial edition of Leviathan.) Above that, we see a bishop's mitre. Finally, we see a church. The military pictures are arranged to correspond with each of the ecclesiastical pictures--a military battle, trophies of war, a cannon, a commander's crown, and a fortress.

These pictures convey visually Hobbes's teaching that a state of nature without government must become a state of war, in which human life must be "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short." Therefore, to escape such a condition, any government is better than no government. And a highly centralized government with absolutely sovereign power is best of all.

Some people have claimed that the recent history of weak or failed states (like Somalia, for example) confirms Hobbes's teaching. But is that really true? Or does some of this history suggest that having no government can be better than having a predatory government?

I will take up these questions in my next post.

A few of my posts on Hobbes can be found here, here, here, and here.

Sunday, January 12, 2014

John C. Calhoun's Evolutionary Science of Human Nature, Liberty, and Race

John C. Calhoun (1782-1850) was one of the most prominent American political leaders in the first half of the 19th century. He was elected as a Congressman from South Carolina in 1810. He served as Secretary of War (1817-1824), Secretary of State (1844-1845), Vice-President (1825-1832), and Senator from South Carolina (1832-1844, 1845-1850). He was first nominated for President in 1821, and he was considered a serious candidate for the Presidency in every presidential election from 1824 to 1848. In the debates over the nature of the American Union, he became the leading spokesman for States' rights, the American South, and the southern institution of slavery. South Carolina's Declaration of Secession in December of 1860 followed closely Calhoun's logic for the right of a State to secede from the Union.

Calhoun was one of those rare politicians who was also a political philosopher. He claimed to have developed a true science of politics in which he explained the evolutionary history of government and constitutionalism as constrained by a universal human nature. He elaborated this political science in many writings and speeches, but most fully in two posthumously published books--A Disquisition on Government and A Discourse on the Constitution and Government of the United States. One of the best collections of his writing as published by the Liberty Fund and edited by Ross Lence is available online.

Although it is not Darwinian, Calhoun's political science follows the structure of a Darwinian political science in which human nature constrains but does not determine human culture and human judgment. Moreover, Calhoun suggests, the science of human nature that lies at the foundation of political science is part of a general biological "law of animated existence" that embraces all animals.

Many people today scornfully dismiss Calhoun's political science because they find his defense of slavery abhorrent. But this ignores Calhoun's deep insight in understanding the problem of majority tyranny in a democracy and in developing an attractive solution to that problem--the concurrent majority. His proposed solution ultimately fails, however, because he failed to see how democratic republicanism depends upon a natural human equality of liberty that creates tragic conflicts of interest that can never be perfectly resolved by constitutional forms.

He also failed to see how the biological equality of human beings as belonging to the same species refutes any defense of slavery as founded in racial science.

THE LAW OF HUMAN NATURE AND OF ANIMAL LIFE

In the Disquisition, Calhoun looks to the "constitution or law of our nature" as the foundation for the "science of government" that is as solid as the law of gravitational attraction is for the science of astronomy.

This "law of our nature" is constituted by three "incontestable facts" about human nature (Lence edition, 5-6)--natural sociality, the natural necessity for government to perfect that sociality, and the natural tendency for individual feelings to be stronger than social feelings, which makes government necessary for resolving conflict between individuals.

First, human beings are by nature social beings, because they everywhere associate with other members of their species, and they could not satisfy their physical, moral, and intellectual wants without social life. Human beings have never been found to exist as purely solitary animals.

Second, this social state requires government. No human society, even the most savage, has ever been found without government of some kind.

Third, the reason that society cannot exist without government is that while a human being feels what affects others as well as what affects himself, he feels more intensely and directly what affects himself than what affects others. This throws individuals into conflict, because each person is inclined to sacrifice the interests of others to his own interests. This tendency to universal conflict would destroy society if there were no controlling power to mediate conflict, and this controlling power is government.

Calhoun recognizes, however, that there are some peculiar circumstances and conditions in which the social feelings can override the individual feelings--as in a mother's care of her infant and in rare cases where unusual individuals are shaped by education and habituation to care more for others than themselves (6).

Calhoun understands this law of human nature as part of a general law of animal life:

Like other animals, human beings have evolved instincts for self-preservation, so that they feel more directly what affects themselves than what affects others. And yet as social animals who are born dependent on parental care, and who live in social groups, human beings extend their care for themselves into care for others bound to them by ties of kinship, mutuality, and reciprocity.

Although they are social animals, human beings do not show the perfect sociality of colonial invertebrates (such as corals, the Portuguese man-of-war, or sponges), because human beings are not genetically identical. As products of a tense balance of individual selection and group selection, human beings show a complex interaction of individual competitiveness and group loyalty. Even in small bands of hunter-gatherers, where one might expect a harmony of interests, there are individual conflicts that require mediation through some sort of informal governmental order. As is true for other social animals, government is required to resolve conflicts of interest among human beings, but this governmental resolution of conflict must always be imperfect, because there will never be any perfect harmony of interests.

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW AND THE CONCURRENT MAJORITY

That same law of human nature that makes government necessary to secure social order also gives government a natural tendency to abuse of its powers, because those who have the powers of government will be inclined by their individual interests to use those powers for their own advantage contrary to the common good. For that reason, Calhoun explains, we need a constitutional structure to organize the powers of government to prevent their abuse. "Having its origin in the same principle of our nature, constitution stands to government, as government stands to society; and, as the end for which society is ordained, would be defeated without government, so that for which government is ordained would, in great measure, be defeated without constitution" (9). But while government in some form arises naturally in all human societies, constitution is a more artificial human contrivance that is more difficult to form.

Just as the natural tendency of individuals to resist being attacked or exploited leads them to establish government to protect them against the aggression of other individuals, so does this same natural resistance to unjust aggression lead them to establish constitutional structures to protect them against the abuse of government by the rulers. The fundamental principle here is countervailing power. "Power can only be resisted by power and tendency by tendency" (12).

Traditionally, beginning in ancient Greece, the constitutional forms of government have been distinguished as rule by one (monarchy), by few (aristocracy), or by many (democracy), or by some mixture of one, few, and many.

Anarchists argue for rule by none, so that there would be no abuse of the powers of government over society, because there would be society but no government. Calhoun dismisses this as impossible based on the evidence of history--that all human societies, no matter how primitive, have had government in some form. Modern evolutionary political anthropology confirms this: even hunter-gatherer bands without any formal government have informal leadership by some individuals. Even among other political animals, such as chimpanzees, there are dominance hierarchies in which alpha individuals exercise control over society.

Another possibility is rule by all--that is, organize governmental power so that everyone in a society either concurs in governmental decisions or can exercise a veto over decisions, and thus government rules by unanimous consent, and no one can be oppressed by others. This is what Calhoun defends in his idea of concurrent majority.

Calhoun accepts electoral democracy with majority-rule as a primary restraint on the abuse of governmental powers, because this forces the rulers to win the support of the majority in society. But this fails to solve the problem of majority tyranny over minorities.

One famous proposed solution to the tyranny of the majority is James Madison's argument (in Federalist number 10) for an extended republic in which the great multiplicity of interests will make is unlikely that any unjust majority can form. But Calhoun argues that political parties competing for majority control of the government will foster the formation of coalitions in which diverse interests find common cause in becoming a winning majority that can exploit the losing minorities.

This can be seen in the unequal fiscal actions of government that divide every community into two classes--taxpayers and tax-consumers. Imagine a community of five individuals under a government controlled by majority rule (18-19, 446-51). Imagine that the government collects an equal amount of revenue from each of the five, so that there is equality in the raising of revenue. Won't there be an incentive for three of the five to form a majority coalition that can appropriate all of that revenue for the benefit of the three, and thus the minority of two has no protection against exploitation?

Three of the five constitute a "numerical majority" that can oppress the minority. The only protection for the minority, Calhoun argues, is a "concurrent majority" that would "give to each division or interest, through its appropriate organ, either a concurrent voice in making and executing the laws, or a veto on their execution," which would require "taking the sense of each interest or portion of the community" (21).

Calhoun saw this problem manifest in the American Union. If the Northern States have a majority control of the federal government, they can use that power to legislate federal tariffs that favor the interests of the North at the expense of the South; or they can use that majoritarian power to attack the Southern institution of slavery, even though those in the South see these policies as unconstitutional. The only effective protection against such majority tyranny, Calhoun concluded, was to recognize that each State was sovereign in its power to veto any federal policy that it saw to be unconstitutional. In response to such State nullification of federal laws, 3/4 of the States could use their constitutional power for amending the constitution to declare whether this nullification was correct as an interpretation of the Constitution. The State could then acquiesce to this decision, or it could invoke its right to secede from the Union. This threat of secession and disunion would be a powerful incentive for finding a compromise acceptable to all.

Before the Civil War, the United States was a deeply divided society because of the conflicting sectional interests of North and South, in which it appeared that the Northern section was becoming a permanent majority interest that could use majority rule to dominate the Union. The same situation can arise in other societies deeply divided by racial, ethnic, religious, linguistic, and other cultural differences. In such societies, those who belong to minority groups might find Calhoun's proposal for a concurrent majority to be powerfully attractive. After all, why can't we agree that the common good is best achieved in social orders where each interest has a veto power over every major policy, so that policies must arise by rule of consensus, and no group can exploit any other group?

There are, however, serious problems with Calhoun's consensus model of democracy. The best survey of those problems is James Read's book Majority Rule Versus Consensus: The Political Thought of John C. Calhoun (University Press of Kansas, 2009), which includes studies of how Calhoun's system might apply not only to the United States before the Civil War but also to other deeply divided societies (such as Northern Ireland, the former Yugoslavia, and South Africa). By contrast, the best philosophical defense of Calhoun's reasoning is Lee Cheek's Calhoun and Popular Rule: The Political Theory of the Disquisition and Discourse (University of Missouri Press, 2001).

Read identifies three major problems--the problem of anarchy or deadlock, the problem of minority rule, and the problem of infinite regression in vetoes.

First, if each "portion or interest" of a community has the right to veto decisions of the government, won't this block all decisions and thus throw the society into anarchy? Calhoun's answer is no, because the very threat of anarchy or deadlock will force all interests to reach a compromise satisfying to all to avoid the harm to all coming from a failure to act. He thinks juries illustrate this. The requirement that juries reach a unanimous decision gives a veto power to each juror. But most of the time, juries reach a decision because their desire to avoid deadlock moves them to deliberate until they all agree on a decision.

This jury analogy is not persuasive, however, because jurors are not supposed to have a personal stake in the outcome of the case, while legislators are motivated by personal interests, either their own or those of their constituents, that will be affected by their decisions. And while legislators might feel social pressure to avoid deadlock, they might also feel social pressure not to compromise.

Second, if a minority can veto the decision of the majority, won't that allow the minority to rule over the majority? Calhoun's answer is no, because the power of a minority to block action is not the same as the power to impose action. But, as Read indicates, it is often the case that a minority imposes its will precisely by blocking action, because governmental inaction is itself a policy. So, for example, the blocking of a protective tariff would impose a policy against protective tariffs.

Third, if every "portion or interest" is to have a veto power, how do we identify that "portion or interest"? Or to put the question another way, where do veto rights stop? If one minority group has a veto power, why don't the minorities within that group also have a veto power over the group? Read asks: "What prevents an infinite regress of vetoes-within-vetoes by minorities-within-minorities?"

For example, when Calhoun was leading the movement for South Carolina to nullify the federal tariff, he supported a requirement that all office holders in South Carolina would have to take an oath to support this nullification. This provoked the Unionist minority in South Carolina into charging that this was majority tyranny.

This points to what I regard as the most fundamental problem for Calhoun's unanimity principle. On the one hand, Calhoun assumes a diversity of interests in which each interest is inclined to exploit the others, which requires a rule of unanimity to avoid exploitation. On the other hand, he assumes that each interest is internally so homogeneous in its shared interest that it can be governed by simple majority rule without any tendency to exploit a minority, and consequently, "every individual of every interest might trust, with confidence, its majority or appropriate organ, against that of every other interest" (23). Calhoun never resolves this contradiction in his reasoning.

Calhoun says that wherever the interests of a community are dissimilar, the rule by a simple majority cannot produce justice. And such a "dissimilarity of interests" is "to be found in every community, in a greater or less degree, however small or homogeneous" (373). But if even the smallest and most homogeneous groups have such diverse interests that lead to conflict, then no group can be trusted to have a veto power that is not checked by vetoes from within the group, and thus we are thrown into an infinite regress for which the only stopping point is to grant a veto power to every individual person.

The very "law of our nature" that Calhoun invokes includes the natural diversity of individuals, no two of whom are identical, which creates individual conflict that can never be completely overcome by our natural sociality. In this conflict of individual interests, each individual is naturally inclined to resist exploitative rule by others, and thus each individual is equal to the others in demanding the liberty to govern oneself. Calhoun seems to concede this when he declares that "every individual has the right to govern himself" (373). But he denies this in his defense of slavery.

SLAVERY

"It is a great and dangerous error to suppose that all people are equally entitled to liberty," Calhoun insists. Liberty is "a reward to be earned, . . . a reward reserved for the intelligent, the patriotic, the virtuous and deserving--and not a boon to be bestowed on a people too ignorant, degraded and vicious, to be capable either of appreciating or of enjoying it" (42). This implies that those with ruling power must identify those who deserve liberty and those who don't. But according to Calhoun's science of human nature, no human being can be trusted with such power.