Chinese Footbinding: "Lotus Feet" and "Lotus Shoes"

Having written in my previous post about the Darwinian ethics of beauty as an evolved natural desire, I can imagine that many readers want to object that there is no universal moral standard of beauty, because there is no agreement across individuals or across cultures about what counts as beauty. If beauty is in the eye of the beholder, then aren't judgments of beauty subjective, arbitrary, and culturally relative?

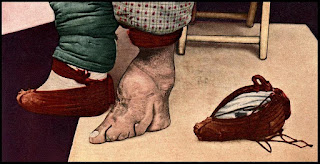

Chinese footbinding and female circumcision are often mentioned as two examples of this. For almost a thousand years, many Chinese women mutilated their feet by binding their toes under the soles of their feet, breaking bones and crippling themselves so badly that it was hard for them to walk. They did this because they thought women with tiny feet were beautiful, and men would not marry them if their feet were unbound. Most of us find this grotesquely ugly.

Similarly, hundreds of millions of women across central Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia have had their genitals mutilated by their mothers when they were children: their clitorises were cut off (clitoridectomy), and sometimes the sides of the vulva were sewn together (infibulation), leaving only a tiny hole for the flow of urine and menstrual blood. To make sexual intercourse possible, their husbands must rip them open. These women believe that clitoridectomy and infibulation make their genitals beautiful, and that men will not marry women who have not gone through this. Once again, most of us find this repulsive rather than beautiful.

I contend, however, that the mere fact of moral disagreement about beauty and other human goods does not prove that there are no natural, universal standards for moral debate. I begin by identifying the four sources of moral disagreement and arguing that such moral controversy allows us to engage in moral deliberation in which we appeal to a universal pattern of natural human desires as the norm for settling our disputes. I then turn to Chinese footbinding and female circumcision as illustrations of moral debates that can be resolved by moral persuasion.

MORAL DISAGREEMENT

There are four sources of moral disagreement: fallible beliefs about circumstances, fallible beliefs about desires, variable circumstances, and variable desires. Consequently, ethics is not a demonstrative science in which one properly seeks certainty and precision. Because of its uncertainty and imprecision, ethics requires the sort of practical judgment rooted in experience--what Aristotle and the Greeks called prudence (phronesis)--that cannot be reduced to abstract rules. But still, the ultimate standard for ethics is the pattern of natural desires that belongs to our evolved human nature.

Fallible beliefs about circumstances. Moral judgment is often uncertain and imprecise because our knowledge of the circumstances of action is uncertain and imprecise. We often disagree about moral questions, even when we agree in our principles, because we have differing views of the relevant circumstances. In fact, much of our moral reasoning is devoted to gathering and assessing the facts pertinent to our practical decisions.

For example, if parents believe that the social circumstances of their life make it impossible for their daughters to marry well if they are not mutilated (by footbinding or female circumcision), then many parents will force their daughters to be mutilated. But if parents believe there are ways to resist or change those social circumstances, so that their daughters can marry well without being mutilated, they will do so.

Fallible beliefs about desires. The good is the desirable. But we are often unsure about what we truly desire, because we often desire what we discover is not truly desirable. Even when we think we know what we desire at some particular moment, it is not always clear whether satisfying that momentary desire will impede the satisfaction of a more important desire in the future. Much of our moral deliberation with ourselves and with others requires reasoning about the consistency or contradiction of diverse desires over a complete life. Furthermore, we often disagree about whether individually or socially arbitrary desires properly specify our natural desires.

For example, while some women in some societies have believed that to satisfy their natural desires for sexual mating, familial bonding, and having children, they must have their genitals or their feet mutilated, these customary desires for female genital mutilation and female footbinding are founded on mistaken beliefs that frustrate the natural desires of both men and women.

Variable circumstances. The variability in the practical circumstances that distinguish one individual from another and one society from another requires variability in our moral judgments. Although the pattern of natural human desires is universal, satisfying those desires in different individual and social circumstances requires different patterns of conduct appropriate to the circumstances.

For example, in societies with social conventions that make female footbinding or female circumcision a requirement for a woman attracting a good husband, women cannot violate those conventions without being punished, which makes these conventions self-enforcing. Consequently, to succeed in gradually abolishing those conventions, women and men will have to join social movements in which many people agree that they will not impose footbinding or circumcision on their daughters, and they will not allow their sons to marry women with bound feet or mutilated genitals.

Variable desires. There is both normal and abnormal variation in human desires. By "normal," I mean the central tendency in the distribution of a trait. By "abnormal," I mean a wide deviance from the central tendency. The normal variation arises from age, sexual identity, and individual temperament. Natural human diversity is such that on average the young do not have exactly the same desires as the old, men do not have exactly the same desires as women, and individuals with one temperament do not have exactly the same desires as those with another temperament. (I have written about the importance of individuality, historicity, and animal personalities in biological nature.)

The abnormal variation in desires arises from abnormality in innate dispositions or in social circumstances. For example, while human beings are normally social animals with social desires that incline them to sympathize with the pleasures and pains of those close to them, a few human beings are innately predisposed to become psychopaths who do not feel these sympathetic emotions. Consequently, the most extreme psychopaths are moral strangers to the rest of us, because they do not share our moral sentiments; and to protect ourselves from them, we must either ostracize them (lock them up) or execute them. (I have written about the biological psychology of psychopaths.) And sometimes abnormal social circumstances such as the customs of female footbinding and female circumcision promote arbitrary desires that frustrate natural desires.

CHINESE FOOTBINDING

In China, from the Song dynasty (960-1279) to the Qing dynasty (1636-1912), many Han Chinese girls and women had their feet regularly wrapped tightly to keep their feet small. Oten toes were broken as the feet were rolled into an morbidly tight ball. The ideal was to compress the arch of the foot, even breaking it, so that the foot was no longer than about 4.5 inches long, although this ideal was rarely achieved. Bound feet were thought to be beautiful and sexually attractive to men, so that men preferred to marry women with bound feet, and unbound natural feet were regarded as ugly and disgusting. Footbinding caused many physiological and orthopedic maladies for these women throughout their lives, including difficulty in walking that reduced their physical activity (Levy 1966; Ko 2005).

This practice of footbinding was originally concentrated among elite Han Chinese, but over the years it spread to other classes. Although there is little data about the number of women who had footbound feet, there were probably at least one or two hundred million footbound women. And yet although this custom of footbinding was traditional for many centuries in China, it was largely abolished within a few decades around the beginning of the twentieth century.

In the efforts of social scientists to explain the origin, maintenance, and cessation of Chinese female footbinding, there have been two prominent theories. According to the Hypergamy Hypothesis, parents used footbinding to increase the likelihood that their daughters would marry up (to richer and higher status men) at higher rates in open marriage markets in competition with natural-footed girls. It began with Midred Dickemann's papers on female claustration, female genital mutilation, and footbinding (1979, 1991, 1997).

Dickemann's insight was that hypergamous marriage was rooted in evolved mate preferences. Men (on average) want to mate with women who show the physical beauty of youthful fertility; and in long-term mating, men want women who will assure them of paternal certainty, so that the men are not cuckolded. Women (on average) want to mate with men who have the wealth and status to provide for them and their offspring; and to persuade men to make a long-term investment in them and their children, women will provide cues of sexual fidelity, particularly for the most desirable men. Hypergamy becomes especially important in societies that are highly stratified, that have high patriarchal inequality, and that practice polygyny (multiple wives). High-status wealthy men have the resources to outcompete men with less resources in winning the most desirable young brides. In such circumstances, young women will often prefer to be a second or third wife of a wealthy man rather than the only wife of a poor man.

Although all men have faced the problem of paternal uncertainty (especially before DNA testing)--not knowing for sure that they are the biological fathers of the children born to their wives--this problem becomes acute for polygynous men who have multiple wives to guard. And, again, these men will want to mate with women who show the signs of sexual fidelity.

All of these conditions are true for traditional China. And in ancient China, it was believed that binding the feet of women would reduce the chances of there being unfaithful to their husbands, because women with bound feet have less physical mobility, and thus they are less likely to wander away from home to have sexual trysts. Bound feet were also perceived as beautiful because men prefer women with small feet. Therefore, Chinese parents who wanted their daughters to marry well would bind their feet so that they could outcompete natural-footed women in the marital competition for high-ranking men. Daughters often resisted being bound and complained about the pain and suffering it caused, but parents insisted that without this they could never marry well.

This is the Hypergamy Hypothesis that evolutionary social scientists have offered to explain the origin and maintenance of Chinese footbinding. This hypothesis can also explain the cessation of footbinding in the early decades of the twentieth century, once the social circumstances changed so that natural-footed women could marry well.

Over the past thirty years, a few social scientists have offered an alternative to the Hypergamy Hypothesis in explaining Chinese footbinding--the Labor Market Hypothesis. Melissa Brown, Laurel Bossen, and Hill Gates have been its leading proponents (Bossen and Gates 2017; Brown 2016; Brown et al. 2012; Brown and Satterthwaite-Hillips 2018). The idea is that footbinding was a form of labor control by parents to use their daughters for handicraft work within the home--carding cotton, spinning thread, and twisting hemp that brought in cash or goods necessary for the survival of the family. As Brown says: "five-year-olds like to run and play, not sit in one place for the hours required to produce such quantities of thread (or other products). By making it hurt to walk, footbinding served as labor control to keep girls at their handwork" (Brown 2016, 517). Brown and her colleagues can then explain the cessation of footbinding beginning at the end of the nineteenth century by saying that this was when the mechanized production of cloth and its distribution through railways eliminated the need for such handicraft work. They also try to show the falsity of the Hypergamy Hypothesis by presenting evidence that there was no correlation between footbinding and marrying up.

It is difficult to test these two hypotheses against one another because there is so little quantifiable data about footbinding in Chinese history. Brown, Bossen, and Gates have assembled a database based upon interviews with elderly Chinese women at the end of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st century. In the early 1990s, Gates interviewed women in Sichuan Province. In 2006-2011, Brown and Bossen interviewed women in three other regions of China--the Central, North, and Southwest. These were all inland and primarily rural areas, because it was only here that there were numbers of living women at the end of the 20th century who had experienced footbinding, since footbinding had been ended in coastal areas and urban centers before these living women had been born. These elderly Chinese women were asked a series of questions about their experiences in growing up in China. Brown, Bossen, and Gates built their database through a sample of these participants: 36 participants from the Central region was added to 261 from the North and 142 from the South, for a total of 439 participants; this was then added to the much larger total from Sichuan of 3,275. Thus, they had a grand total of 3,714.

From their analysis of this data, Brown, Bossen, and Gates conclude: "for most regions, we found no statistically significant difference between the chances of a footbound girl versus a not-bound girl in marrying into a wealthier household, despite a common cultural belief that footbinding would improve girls' marital prospects. We do find regional variation: Sichuan showed a significant relation between footbinding and marital mobility" (Brown et al. 2012, 1035). They also say: "For most women, throughout most of the 20th century, FB [footbinding] made no significant difference in their ability either to marry at all or their ability to marry 'up'" (Brown and Satterthwaite-Phillips 2018, 2). They also conclude that there was a correlation between the footbinding of daughters and their handicraft labor. They claim that this refutes the Hypergamy Hypothesis and confirms the Labor Market Hypothesis for explaining footbinding.

But notice the contradiction in what they say here. On the one hand, "for most women," there was no significant correlation between footbinding and marrying up. On the other hand, they concede that there was a significant correlation between footbinding and marrying up among their Sichuan participants, who comprised 87% of their total number of participants!

Ryan Nichols has pointed to this contradiction as one of the many weaknesses in the reasoning of Brown, Bossen, and Gates. They obfuscate this contradiction by saying that "for most regions," there was no correlation between footbinding and hypergamy, which obscures the fact that for most of their participants (particularly those in Sichuan), there was a correlation (Ryan 2021; Chowdhury, Zhang, and Nichols 2022).

By saying that "for most regions" (that is, three out of four regions), there was no significant correlation between footbinding and marrying up, Brown, Bossen, and Gates treat the Central region (with only 44 total participants, of whom only 6 were footbound) as evidentially equal to the Sichuan region (with 3,327 total participants, of whom 994 were footbound). As Nichols points out, readers have to carefully study the actual numbers to see how the language of "for most regions" distorts the evidence.

Moreover, as Nichols suggests, the correlation between footboundness and hypergamy would probably have been even higher than it is if Brown, Bossen, and Gates had not reduced the data prior to testing by throwing out all data from cohorts of women in which a majority were not footbound.

Nichols has identified other flaws in their reasoning. Brown, Bossen, and Gates speak about the Labor Market Hypothesis and the Hypergamy Hypothesis as if they were mutually exclusive. But this ignores the possibility that once parents have decided that footbinding will improve the mating prospects of their daughters, they might use their daughter's labor in handicrafts as a strategy for mitigating their costs. Consequently, the Labor Market Hypothesis and the Hypergamy Hypothesis are mutually compatible. Brown, Bossen, and Gates say nothing about this possibility.

They also ignore the fact that to test the Hypergamy Hypothesis, there must be an open marriage market in which there is sufficient competition between footbound and natural-footed women. If there is a largely closed market, in which almost all of the women are footbound, then there is no test for the Hypergamy Hypothesis. Notably, in the Sichuan data, there is a slightly more open market, because footbound girls were less than 90% of birth cohorts.

This is a devastating critique of the attempt to refute the Hypergamy Hypothesis. As far as I know, Brown, Bossen, and Gates have never responded to this critique. I have sent messages to them asking for some reply to Nichols. Brown and Gates answered my messages but offered no reply. Brown indicated that she might write a reply sometime in the future.

THE MORAL DEBATE OVER FOOTBINDING

Consider now how our moral judgment about Chinese footbinding can be based on the four sources of moral disagreement: fallible beliefs about circumstances, fallible beliefs about desires, variable circumstances, and variable desires.

Parents naturally desire that their daughters should be mated with good husbands who will provide well for their daughters and their children. So if parents believe that the circumstances in their society make it unlikely that their daughters can marry well if their feet are not bound, then many parents will force footbinding on their children. But this belief can be mistaken.

Indeed, we know that across traditional China, there was great variability in the practice of footbinding across time, region, and class. Most Chinese parents did not bind the feet of their daughters because they did not believe this was necessary for the daughters to marry well, and that it would impose unnecessary suffering on their daughters. From the origins of the practice in the Song dynasty, there were scholars who criticized the practice as wrong.

Other than the Han Chinese, most Chinese ethnic groups--such as the Manchus, Mongols, and Tibetans--did not engage in footbinding. Even among the Han, many Han Chinese (such as the Hakka Han) rejected footbinding. Moreover, those Chinese parents who did practice footbinding provoked resistance from their daughters. Many footbound daughters loosened their bindings or ceased binding after marriage. Most bindings were not maintained over an entire life. When Brown, Bossen, and Gates asked their interviewees about whether they found footbinding desirable, almost half of them said it was not, and only about a fifth of them said they accepted it in some manner. So there was widespread disagreement among the Chinese as to whether footbinding was desirable, which allowed for a moral debate, in which the critics of footbinding could argue that it frustrated natural human desires.

A popular campaign against footbinding was based on the argument that footbinding was "unnatural," and that "natural feet" were desirable for both women and men. The first Natural Foot Society was founded in 1895. Then many natural foot societies began to appear. This and similar groups engaged in three kinds of activity (Levy 1966; Mackie 1996). They promoted an educational campaign on the advantages of natural feet and the disadvantages of bound feet. They showed that the rest of the world did not practice footbinding, and that China was losing respect in the world because of it. Finally, following the example of American temperance societies campaigning against alcohol, members of natural foot societies pledged neither to bind their daughters nor to allow their sons to marry women with bound feet.

As suggested by Gerry Mackie's evolutionary game-theoretic analysis, footbinding was an evolutionarily stable strategy for parents only when it was a self-enforcing social convention. As long as this convention was generally accepted in a social group, parents who tried to violate it by refusing to bind their daughters' feet would be punished because their daughters could not be married to the most desirable men. But once enough parents could be persuaded to join natural foot societies and pledge not to bind their daughters' feet nor to allow their sons to marry footbound women, they created a new mating market in which natural-footed women could find good mates.

FEMALE CIRCUMCISION

There has been a similar moral debate over the desirability of female circumcision, in which parents mutilate the genitals of their daughters because they think this will make them more desirable for marriage. Actually, the debate is even evident in the dispute over the proper terminology for this practice. Calling it "female circumcision" suggests that it is no worse than "male circumcision." But critics insist that clitoridectomy and infibulation are much more harmful to women than is cutting off the foreskin is for men. Some people prefer the more neutral language of "female genital cutting."

Since I have already written a series of posts on female circumcision, I don't need to say much more about it here. I will only point out that the moral debate over female circumcision shows the same character as the moral debate over footbinding: it's a dispute over fallible beliefs about circumstances, fallible beliefs about desires, variable circumstances, and variable desires.

For example, consider the debate between Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Fuambai Ahmadi over the morality of female circumcision. Ali was born in Somalia. She was raised as a Muslim, living in Somalia, Saudi Arabia, Ethiopia, and Kenya. As a child, her genitals were mutilated by family members practicing "female circumcision" as a way of ensuring female virginity by excising the clitoris and sewing up the vagina. In 1992, she fled to Holland as she ran away from a forced marriage to a cousin who was a Somali Canadian. Now, Ali has become a fervent opponent of female genital mutilation and the Islamic beliefs that support it. She also denounces those feminist multicultural relativists who argue that some African women have chosen to embrace the cultural tradition of female circumcision, and that any criticism of this by Westerners is cultural imperialism. Ali rejects this multicultural relativism by appealing to universal human rights based on natural human desires that set a standard for condemning traditional practices like genital mutilation.

On the other side of this debate is Fuambai Ahmadu, who was born in Sierra Leone and reared in the United States, and became an anthropologist who has studied female circumcision among her native Kono ethnic group in Sierra Leone. At age 22, she decided to travel back to her native village so that she herself could be circumcised. She now provokes intense controversy by writing and lecturing in which she criticizes people like Ali for their campaign against female circumcision as Euroamerican cultural imperialism and ethnocentrism. She claims that she herself has not felt any impediment to her sexual life or any other harm from her circumcision, which was an excision of her clitoris. Moreover, she insists that most circumcised African women find deep satisfaction in their circumcision, which refutes all of the reports about the supposed harms from female circumcision.

The ultimate question in this debate is whether female circumcision is truly desirable for those African mothers and daughters who have practiced it. Ali says it is not. Ahmadu says it is. This is a factual question. For various reasons, I think Ali makes the better argument.

One reason for this is that Ahmadu's position becomes confusingly incoherent. On the one hand, she says that the African mothers and daughters engaged in female circumcision find it desirable. On the other hand, she admits that many African women have rejected it, and many have organized themselves into groups pledging to one another that they will not circumcize their daughters or allow their sons to marry a circumcized girl. And there is evidence of a drastic drop in Africa in the rate of female genital mutilation, comparable to what happened in China with the cessation of footbinding.

Ahmadu even admits that forcing girls to be circumcized is wrong, and that women should remain uncircumcized until they are young adults and able to decide for themselves whether they want this.

Ahmadu is also confusing about her own decision as an adult to be circumcized in her African tribe. She says that she has not lost the capacity for clitoral orgasm, which makes us suspect that she did not have her clitoris completely cut off. She might have had only a ritual scratch or mark on her clitoris. This is one way that African women have avoided the most harmful forms of female circumcision.

In all of this, we see that if the good is the desirable, then we can debate the goodness of practices like footbinding and female circumcision by judging whether they are truly desirable in satisfying the evolved natural desires of universal human nature.

REFERENCES

Bossen, Laurel, and Hill Gates. 2017. Bound Feet, Young Hands: Tracking the Demise of Footbinding in Village China. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Brown, Melissa. 2016. "Footbinding, Industrialization, and Evolutionary Explanation: An Empirical Illustration of Niche Construction and Social Inheritance." Human Nature 27: 501-532.

Brown, Melissa, Laurel Bossen, Hill Gates, and Damian Satterthwaite-Phillips. 2012. "Marriage Mobility and Footbinding in Pre-1949 Rural China: A Reconstruction of Gender, Economics, and Meaning in Social Causation." The Journal of Asian Studies 71: 1035-1067.

Brown, Melissa, and Damian Satterthwaite-Phillips. 2018. "Economic Correlates of Footbinding: Implications for the Importance of Chinese Daughters' Labor." PLoS ONE 13 (9): e0201337.

Chowdhury, Laura Smith, Yile Zhang, and Ryan Nichols. 2022. "Footbinding and Its Cessation: An Agent-Based Model Adjudication of the Labor Market and Evolutionary Sciences Hypotheses." Evolution and Human Behavior 43: 475-489.

Dickemann, Mildred. 1979. "The Ecology of Mating Systems in Hypergynous Dowry Societies." Social Science Information 18: 163-195.

Dickemann, Mildred. 1991. "Women, Class, and Dowry." American Anthropologist 93: 944-946.

Dickemann, Mildred. 1997. "Paternal Confidence and Dowry Competition: A Biocultural Analysis of Purdah." In Laura Betzig, ed., Human Nature: A Critical Reader, 311-328. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ko, Dorothy. 2005. Cinderella's Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Levy, Howard. 1966. Chinese Footbinding. New York: Walton Rawls.

Mackie, Gerald. 1996. "Ending Footbinding and Infibulation: A Convention Account." American

Sociological Review 61: 999-1017.

Sociological Review 61: 999-1017.

Nichols, Ryan. 2021. "Footbinding, Hypergamy, and Handcraft Labor: Evaluating the Labor Market Explanation of Footbinding." Evolutionary Psychological Science 7: 315-325.

2 comments:

You've been awfully quiet on the debates surrounding transexualism that have been raging in the culture. Is this because on your theory desiring to be the opposite sex or having your sex organs removed are clearly "unnatural desires" and so would be banned on your theory? You know to publicly claim so would bring down the leftist mob on you so you keep to your usual safe and risk-free modus operandi of exclusively punching right?

I have written many times about transgenderism and intersexuality: https://darwinianconservatism.blogspot.com/search?q=semenya

Post a Comment