THE CREATION OF ADAM'S PREFRONTAL CORTEX

Michelangelo's "Creation of Adam" is his visual depiction of the teaching in Genesis 1:27--"So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them" (KJV). Remarkably, Adam's body is already fully formed, but God is going to transmit to him something essential to his humanity through God's extended finger. Presumably, God is endowing Adam with a human soul. But how exactly is that to happen?

We should notice that Michelangelo chose not to depict another image of Adam's creation from Genesis: "And the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul" (2:7). Michelangelo decided not to show God breathing into Adam's nostrils the breath of life as the source of ensoulment.

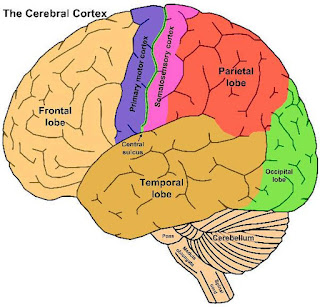

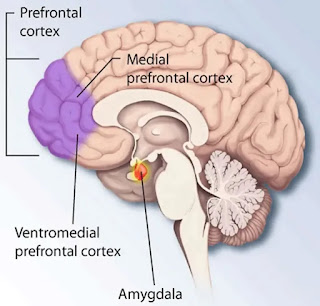

So what is it about the image of God flying through the air and stretching out his arm towards Adam lying on the ground that conveys the emergence of a human soul in Adam? Some neuroscientists have pointed out that one can see a hidden drawing of the human brain in the image of God. And God's right arm is extended through the prefrontal cortex, which is the part of the cerebral cortex responsible for decision-making, planning, creativity, working memory, and language. Previously, I have written about how the liberty or freedom to choose between alternatives is a function of the cerebral cortex, under prefrontal control, in its reciprocal interaction with the environment.

We know that Michelangelo studied human anatomy carefully, and that he dissected human bodies and brains. We know this from his anatomical drawings. (Leonardo da Vinci--a contemporary of Michelangelo's--was also a talented anatomist of the brain.) But of the thousands of Michelangelo's drawings, he destroyed most of them, and only about 600 have survived. Some of these show drawings of the human skull and brain, but none of them show the exact outline of the cerebral cortex that some neuroscientists have seen hidden in Michelangelo's pictures. There is certainly no evidence that Michelangelo understood the cognitive functions of the cerebral cortex and the prefrontal cortex. Seeing a hidden neuroscientific message in Michelangelo's picture seems fanciful.

Nevertheless, we could argue for a modern neuroscientific revision of Michelangelo's picture, in which the image of God could be replaced by the image of the human cerebral cortex. This would not have to be seen as an atheistic revision of the picture. Because if the theistic evolutionists (like Francis Collins, Deborah Haarsma, and the last three Catholic popes) are correct, then God works through the natural laws of evolution to execute His creative design. Some of the theistic evolutionists (like Pope Francis) say that while God works mostly through natural evolution rather than miracles, the creation of the human soul did require an "ontological leap"--a supernatural miracle--that transcended natural evolution. But as I have argued, there are good reasons to believe that the natural evolution of the primate brain can explain the emergence of the soul in the human brain, so that no miracle was required. And yet we still have to wonder what properties of the evolved human brain explain the amazing intellectual and emotional capacities of the human mind.

COUNTING NEURONS

Over the past fifteen years, the research of Suzana Herculano-Houzel, a Brazilian neuroscientist now at Vanderbilt University, has shown how this natural evolution of the human brain can be understood as based on the remarkable number of neurons in the human cerebral cortex, as it has emerged from the evolution of the primate brain, and thus we can see that we were created in the image of other primates, just as Charles Darwin suggested in 1871 in The Descent of Man (Gabi et al. 2016; Herculano-Houzel 2016, 2021; Herculano-Houzel and Lent 2005). I am persuaded by most of what Herculano-Houzel says, although I will identify two points of disagreement with her.

Suzana Herculano-Houzel Counts NeuronsHow many neurons are in the human brain? For many years, the answer from many scientists was 100 billion. But, surprisingly, when Herculano-Houzel began some years ago looking for the original scientific research that provided evidence for this number, she found nothing. She discovered that neuroscientists had repeated this number over and over again without realizing that there was no scientific verification for it.

Moreover, she discovered that scientists had no reliable method for counting brain cells. The most common method for attempting to do this was stereology: virtual three-dimensional probes are placed throughout thin slices of brain tissue from some part of the brain, then the number of cells within the probes are counted, and finally this is extrapolated to the total number of cells in the entire tissue volume. The problem is that this works only for tissues with a relatively homogeneous distribution of cells. In fact, the highly variable density of neurons across different structures of the brain, and even within a single structure, makes stereology impractical for counting the cells in whole brains.

Herculano-Houzel developed a new technique for counting neurons that starts with creating brain soup. She dissects the brain into its anatomically distinct parts--such as the cerebral cortex, the cerebellum, and the olfactory bulbs. She then slices and dices each part into smaller portions. Next, she puts each small part in a tube and uses a detergent that dissolves the cell membranes but leaves the cell nuclei intact. By sliding a piston up and down in the tube, she homogenizes this brain tissue into a soup in which the nuclei are evenly distributed. She stains all the cell nuclei blue so that she can count them under a fluorescent microscope. She then adds an antibody labeled red that binds specifically to a protein expressed in all neuronal cell nuclei, which distinguishes them from other cell nuclei such as glial cells. Going back to the microscope, she can then determine what percentage of all nuclei (stained blue) belong to neurons (now stained red). Finally, she can estimate the number of neurons for each structure of the brain. She has done this in studying the brains of many mammalian animals.

Now she can tell us that the total number of neurons in the whole human brain is not 100 billion but 86 billion. Of that total, 16 billion are in the cerebral cortex, which includes 1.3 billion neurons in the prefrontal cortex. The cerebral cortex is the outer covering of the surfaces of the cerebral hemispheres. The prefrontal cortex covers the front part of the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex located behind the forehead.

FOUR ADVANTAGES

Comparing the numbers of neurons for the human brain with the numbers for other primate brains and other mammalian brains allows Herculano-Houzel to explain the conundrum of how the human brain can be at once so similar to and yet so different from other animal brains. She makes four arguments about how the human brain gives human beings four kinds of advantages in their mental abilities: the primate advantage, the human advantage, the advantage of cooking, and the advantage of cultural learning.

Her claim that differences in cognitive capabilities across species can be explained by differences in the absolute numbers of neurons depends on a fundamental assumption. If neurons are the basic units of brain networks for processing information, and if the networks are structured in similar patterns, then the greater the number of neurons in a network, the greater the capacity of the network for processing information.

The primate advantage. Not surprisingly, larger brains tend to contain more neurons than smaller brains. But different groups of animals show different scaling rules in proportioning brain size to number of neurons. For example, a rodent cortex will have fewer neurons than a primate cortex of similar mass. Primates always concentrate larger numbers of neurons in the brain than rodents of a similar, or even larger, brain size.

Darwin noted that self-consciousness is uniquely human: "It may be freely admitted that no animal is self-conscious, if by this term it is implied, that he reflects on such points, as whence he comes or whither he will go, or what is life and death, and so forth" (Descent, Penguin edition, 105). Morality is also uniquely human: "A moral being is one who is capable of comparing his past and future actions or motives, and of approving or disapproving of them. We have no reason to suppose that any of the lower animals have this capacity. . . . man . . . alone can with certainty be ranked as a moral being" (135). And language is uniquely human: "The habitual use of articulate language is . . . peculiar to man" (107).

Darwin could implicitly affirm such emergent differences in kind without affirming any radical differences in kind. Emergent differences in kind can be explained by natural science as differences in kind that naturally evolve from differences in degree that pass over a critical threshold of complexity. So, for example, we can see the uniquely human capacities for self-consciousness, morality, and language as emerging from the evolutionary increase in the neurons of the primate brain, so that at some critical point in the evolution of our ancestors, the size and complexity of the brain (perhaps particularly in the frontal cortex) reached a point where distinctively human cognitive capacities emerged at higher levels of brain evolution that are not found in other primates. With such emergent differences in kind, there is an underlying unbroken continuity between human beings and their hominid ancestors, so there is no need to posit some supernatural intervention in nature that would create a radical difference in kind in which there is a gap with no underlying continuity.

The symbolic inheritance system is uniquely human because it shows the qualitative leap that defines our humanity as based on our capacity for symbolic thought and communication. Other animals can communicate through signs. But only human beings can communicate through symbols. The evolution of human language was probably crucial for the evolution of symbolism. Symbolic systems allow us to think about abstractions that have little to do with concrete, immediate experiences. Symbolic systems allow human beings to construct a shared imagined reality. These symbolic constructions are often fictional and future-oriented. Art, religion, science, and philosophy are all manifestations of human symbolic evolution.