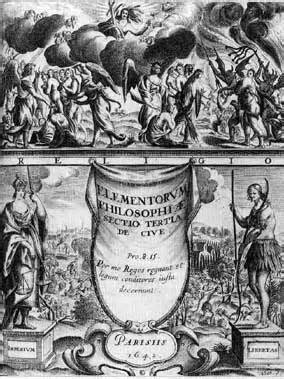

This is the most famous picture in the history of political philosophy, which is the title page for Thomas Hobbes' Leviathan, or The Matter, Forme, and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civill (1651).

As indicated by the Biblical quotation at the very top of the picture--from Job 41:33--Hobbes compares sovereign political power to the Leviathan (probably a giant whale) who is said by God to be so powerful that no power on earth can be compared with him, and he rules as "King of all the children of pride."

In the top half of the picture, Leviathan is depicted as a king holding a staff of authority in his left hand and a sword in his right. The king's body is composed of the human bodies of his subjects, who have their backs turned to the reader as they stare upward at the king's face. Below the king is a settled countryside and a walled city with various buildings, including a church on the king's left side and a fortress on his right.

In the bottom half of the picture, we see the title of the book, and corresponding to the title's indication of a "Commonwealth Ecclesiaticall and Civill," we see a panel of pictures under the king's left arm depicting ecclesiastical authority, and a panel of pictures under his right arm depicting military power and warfare. The ecclesiastical pictures show, at the bottom, a theological dispute. Above that, we see a pair of horns named "Dilemma," a trident named "Syllogism," and three two-pronged forks with the prongs named "Spiritual"/"Temporal," "Direct"/"Indirect," and "Real"/"Intentional." Above that, we see a picture of thunderbolts, perhaps reflecting the phrase of the time concerning "the thunderbolt of excommunication." (Noel Malcolm has suggested this in his magisterial edition of Leviathan.) Above that, we see a bishop's mitre. Finally, we see a church. The military pictures are arranged to correspond with each of the ecclesiastical pictures--a military battle, trophies of war, a cannon, a commander's crown, and a fortress.

These pictures convey visually Hobbes's teaching that a state of nature without government must become a state of war, in which human life must be "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short." Therefore, to escape such a condition, any government is better than no government. And a highly centralized government with absolutely sovereign power is best of all.

Some people have claimed that the recent history of weak or failed states (like Somalia, for example) confirms Hobbes's teaching. But is that really true? Or does some of this history suggest that having no government can be better than having a predatory government?

I will take up these questions in my next post.

A few of my posts on Hobbes can be found here, here, here, and here.

Did you see that (just retired) law professor Ann Althouse just linked to this?

ReplyDeletehttp://althouse.blogspot.com/2017/01/wapo-gets-it-badly-hilariously-wrong.html

I did. That's why I'm here.

ReplyDelete